[置顶] 泰晓 RISC-V 实验箱,配套 30+ 讲嵌入式 Linux 系统开发公开课

从嵌入式系统视角初次展望 RISC-V 虚拟化

Corrector: TinyCorrect v0.1-rc3 - [epw] Title: A First Look at RISC-V Virtualization from an Embedded Systems Perspective Author: Bruno Sá, José Martins, Sandro Pinto@March 27, 2021 Translator: trueptolemy trueptolemy@foxmail.com Date: 2022/08/11 Revisor: Falcon falcon@tinylab.org, Walimis walimis@walimis.org Project: RISC-V Linux 内核剖析 Sponsor: PLCT Lab, ISCAS

Abstract—This article describes the first public implementation and evaluation of the latest version of the RISC-V hypervisor extension (H-extension v0.6.1) specification in a Rocket chip core. To perform a meaningful evaluation for modern multi-core embedded and mixed-criticality systems, we have ported Bao, an open-source static partitioning hypervisor, to RISC-V. We have also extended the RISC-V platform-level interrupt controller (PLIC) to enable direct guest interrupt injection with low and deterministic latency and we have enhanced the timer infrastructure to avoid trap and emulation overheads. Experiments were carried out in FireSim, a cycle-accurate, FPGA-accelerated simulator, and the system was also successfully deployed and tested in a Zynq UltraScale+ MPSoC ZCU104. Our hardware implementation was open-sourced and is currently in use by the RISC-V community towards the ratification of the H-extension specification.

摘要 本文描述了最新版本的 RISC‑V hypervisor 扩展规范(H‑extension v0.6.1,注:本文 v2 版本于 2021/8/16 在 arxiv 上刊登,实际上,截止到 2022/8/19,RISC-V 社区已经发布了 H-extension v1.0)在 Rocket 芯片内核中的首次公开实现和评估。为了对现代多核嵌入式和混合关键性系统进行有意义的评估,我们将 Bao(一个开源静态分区 hypervisor)移植到 RISC‑V。我们还扩展了 RISC‑V 平台级中断控制器(PLIC)以启用具有低延迟和确定性延迟的 Guest 直接中断注入,并且我们增强了计时器基础架构以避免陷入和模拟开销。实验在 FireSim 中进行,这是一个周期精确的 FPGA 加速模拟器,并且该系统还在 Zynq UltraScale+ MPSoC ZCU104 中成功部署和测试。我们的硬件实现是 开源的,目前被 RISC‑V 社区用于批准 H 扩展规范。

Index Terms—Virtualization, RISC-V, H-extension, Hypervisor, Partitioning, Mixed-criticality, Embedded Systems.

关键词 虚拟化、RISC‑V、H 扩展、hypervisor、分区、混合关键性、嵌入式系统。

前言(由译者撰写)

本文为论文《A First Look at RISC-V Virtualization from an Embedded Systems Perspective》的翻译。

这篇论文于 2021/3/27 首次公开在 arxiv 上,后来被发表在了 IEEE Transactions on Computers 上。本文是基于 arxiv 上的 v2 版本进行翻译的。

这篇论文介绍了 RISC-V 虚拟化扩展(H-extension)的 v0.6.1 版本在 Rocket 芯片上的实现。这是 H-扩展的首次实现,也是迄今为止唯一开源的实现。

截至目前,支持 H-扩展的硬件实现包括本文介绍的 Rocket(FPGA 实现),De-RISC 的 RV64GC 和 SiFive 的 P650。其中,RV64GC 对 H-扩展的支持宣布于 2021/4/28,这是一个 FPGA 实现,相关实现细节未公开。P650 是首款公开宣布将支持 H-扩展的商用芯片,发布于 2021/12/2,目前仍未上市。

本文主要包含如下三部分:

- H-扩展和 Rocket 芯片介绍(第 1 节到第 3 节);

- Rocket 芯片上中断虚拟化的增强以及 Bao hypervisor 在 RISC-V 上的移植(第 4 节到第 5 节);

- H-扩展性能评估和讨论(第 6 节到第 9 节)。

介绍(INTRODUCTION)

In the last decade, virtualization has become a key enabling technology for servers, but also for several embedded industries such as the automotive and industrial control [1], [2]. In the embedded space, the number of requirements has been steadily increasing for the past few years. At the same time, the market pressure to minimize size, weight, power, and cost (SWaP-C) has pushed for the consolidation of several subsystems, typically with distinct criticality levels, onto the same hardware platform [3], [4]. In response, academia and industry have focused on developing hardware support to assist virtualization (e.g., Arm Virtualization Extensions), and adding upstream support for these technologies in mainstream hypervisor solutions [5], [6].

在过去十年中,虚拟化已成为服务器的关键支持技术,同时也适用于汽车和工业控制等多个嵌入式行业 [1]、[2]。在嵌入式领域,过去几年需求的数量一直在稳步增加。同时,最小化尺寸、重量、功率和成本(SWaP‑C)的市场压力推动了将几个子系统(通常具有不同的关键级别)整合到同一个硬件平台上 [3]、[4] 的扩展规范中。作为回应,学术界和工业界专注于开发硬件支持以协助虚拟化(例如,Arm Virtualization Extensions),并在主流 hypervisor 解决方案中增加对这些技术的上游支持 [5]、[6]。

Embedded software stacks are progressively targeting powerful multi-core platforms, endowed with complex memory hierarchies [7], [8]. Despite the logical CPU and memory isolation provided by existing hypervisor layers, there are several challenges and difficulties in proving strong isolation, due to the reciprocal interference caused by micro-architectural resources (e.g., last-level caches, interconnects, and memory controllers) shared among virtual machines (VM) [2], [5].

嵌入式软件栈逐渐瞄准强大的多核平台,其往往具有复杂的内存层次结构 [7]、[8]。尽管现有的 hypervisor 层面上提供了逻辑 CPU 和内存隔离,但由于微架构资源(例如,最后一级缓存、互连和内存控制器)在虚拟机(VM)[2]、[5] 之间的共享引起的相互干扰,在证明强隔离上存在一些挑战和困难。

This issue is particularly relevant for mixed-criticality applications, where security- and safety-critical applications need to coexist along non-critical ones. In this context, a malicious VM can either implement denial-of-service (DoS) attacks by increasing their consumption of a shared resource [3], [9] or to indirectly access other VM’s data leveraging existing timing side-channels [10]. To tackle this issue, industry has been developing specific hardware technology (e.g., Intel Cache Allocation Technology) and the research community have been very active proposing techniques based on cache locking, cache/page coloring, or memory bandwidth reservations [5], [8], [11]–[13].

这个问题对于混合关键应用(mixed-criticality application)至关重要,其中安全应用和安全关键性应用需要与非关键应用程序共存。在这种情况下,恶意 VM 可以通过增加共享资源的消耗来实施拒绝服务(DoS)攻击 [3]、[9],也可以利用现有的时序侧信道(timing side-channel)[10] 间接访问其他 VM 的数据。为了解决这个问题,工业界一直在开发特定的硬件技术(例如,英特尔缓存分配技术),同时研究界也一直非常积极地提出基于缓存锁定、缓存/页面着色或内存带宽预留的技术 [5]、[8]、[11]–[13]。

Recent advances in computing systems have brought to light an innovative computer architecture named RISC-V [14]. RISC-V distinguishes itself from traditional platforms by offering a free and open instruction set architecture (ISA) featuring a modular and highly customizable extension scheme that allows it to scale from tiny embedded microcontrollers up to supercomputers. RISC-V is going towards mainstream adoption under the premise of disrupting the hardware industry such as Linux has disrupted the software industry. As part of the RISC-V privileged architecture specification, hardware virtualization support is specified through the hypervisor extension (H-extension) [15]. The H-extension specification is currently in version 0.6.1, and no ratification has been achieved so far.

计算系统的最新进展带来了一种名为 RISC‑V [14] 的创新计算机架构。RISC-V 通过提供免费和开放的指令集架构(ISA)与传统平台区分开来,该架构具有模块化和高度可定制的扩展方案,允许它从微型嵌入式微控制器扩展到超级计算机。在颠覆未来硬件行业的可能性之下,RISC-V 正逐渐被主流采用,正如同 Linux 颠覆了软件行业。作为 RISC‑V 特权架构规范的一部分,硬件虚拟化支持是通过 hypervisor 扩展(H‑extension)[15] 指定的。H‑extension 规范目前为 0.6.1 版,尚未获得批准。

To date, the H-extension has achieved function completeness with KVM and Xvisor in QEMU. However, none hardware implementation is publicly available yet, and commercial RISC-V cores endowed with hardware virtualization support are not expected to be released in the foreseeable future.

迄今为止,H‑extension 已经在 QEMU 中实现了与 KVM 和 Xvisor 的功能完整性。但是,目前还没有公开可用的硬件实现,并且在可预见的将来,预计不会发布具有硬件虚拟化支持的商业 RISC‑V 内核。

In this work, we share our experience while providing the first public hardware implementation of the latest version of the RISC-V H-extension in the Rocket core [16]. While the specification is intended to fulfil cloud and embedded requirements, we focused our evaluation on modern multi-core embedded and mixed-criticality systems (MCS). In this context, we have ported Bao [2], a type-1, open-source static partitioning hypervisor, to RISC-V.

在这项工作中,我们分享了我们的经验,同时在 Rocket 核心 [16] 中提供了最新版本的 RISC‑V H 扩展的第一个公开硬件实现。虽然该规范旨在满足云和嵌入式要求,但我们将评估重点放在现代多核嵌入式和混合关键性系统(MCS)上。在这种情况下,我们将 Bao(一个 type-1 的开源静态分区 hypervisor)[2] 移植到了 RISC‑V 上。

In the spirit of leveraging the hardware-software codesign opportunity offered by RISC-V, we have also performed a set of architectural enhancements in the interrupt controller and the timer infrastructure aiming at guaranteeing determinism and improving performance, while minimizing interrupt latency and inter-hart interference.

本着利用 RISC‑V 提供的硬件‑软件协同设计机会的精神,我们还在中断控制器和定时器基础设施中进行了一系列架构增强,旨在保证确定性和提高性能,同时最大限 度地减少中断间延迟(interrupt latency)和核间干扰(inter‑hart interference)。

The experiments carried out in FireSim [17], a cycle-accurate, FPGA-accelerated simulator, and corroborated in Zynq UltraScale+ MPSoC ZCU104, demonstrate significant improvements in performance (< 1% overhead for hosted execution) and interrupt latency (> 89% reduction for hosted execution), at a fraction of hardware costs (11% look-up tables and 27-29% registers).

在 FireSim [17] 中进行的实验是一个周期精确的 FPGA 加速模拟器,并在 Zynq UltraScale+ MPSoC ZCU104 中得到证实,证明了性能(托管执行的开销 <1%)和中断延迟(托管执行减少 >89%)的显著改进,只需一小部分硬件成本(11% 的查找表和 27‑29% 的寄存器)。

We released our hardware design as open source 1 and the hardware is currently being used as a reference implementation by the RISC-V International 2 to ratify the H-extension specification.

我们以开源的形式发布了我们的硬件设计 (1),该硬件目前被 RISC-V 国际组织(前 RISC-V 基金会)用作参考实现,来批准正式的 H-扩展规范(注:来自 RISC-V 国际的公开信息)。

In summary, with this work, we make the following contributions: the first public and open source implementation of the latest version of the RISC-V H-extension (v0.6.1) in a Rocket Chip core (Section 3); a set of hardware enhancements, in the platform-level interrupt controller and the architectural timer infrastructure, to tune virtualization support for embedded and mixed-criticality requirements (Section 4); the port of the open source Bao hypervisor for RISC-V (Section 5); the development of an open source ad-hoc testing frame- work that enable the raw functional validation of fine-grain features of the hypervisor specification (Section 6.1); the first public and cycle-accurate evaluation of the H-extension in a RISC-V core. We focused on hardware costs, performance overhead, inter-VM interference, and interrupt latency (Section 6);

总之,通过这项工作,我们做出了以下贡献:

- Rocket Chip 内核中做到了最新版本的 RISC‑V H 扩展(v0.6.1)的首个公开和开源实现(第 3 节);

- 在平台级的中断控制器和架构定时器基础设施中实施了一系列硬件改进,以调整对嵌入式和混合关键性要求的虚拟化支持(第 4 节);

- 为 RISC‑V 实现了开源 hypervisor Bao 的相关移植(第 5 节);

- 开发一个开源的特定的(ad‑hoc)测试框架,可以对 hypervisor 规范的细粒度特性进行原始功能验证(第 6.1 节);

- RISC‑V 内核中 H 扩展的首次公开且周期精确的评估。我们专注于硬件成本、性能开销、VM 间干扰和中断延迟(第 6 节)。

RISC-V 虚拟化支持(RISC-V V IRTUALIZATION S UPPORT)

The RISC-V privilege architecture [15] features originally three privilege levels: (i) machine (M) is the highest privilege mode and intended to execute firmware which should provide the supervisor binary interface (SBI); (ii) supervisor (S) mode is the level where an operating system kernel such as Linux is intended to execute, thus managing virtual-memory leveraging a memory management unit (MMU); and (iii) user (U) for applications.

RISC‑V 特权架构 [15] 最初具有三个特权级别:

- machine (M) 模式是最高特权模式,旨在执行提供 supervisor 层二进制接口(SBI)的固件;

- supervisor (S) 模式是操作系统内核(如 Linux)执行的级别,从而利用内存管理单元(MMU)管理虚拟内存;

- user (U) 模式用于应用程序。

The modularity offered by the ISA allows implementations featuring only M or M/U which are most appropriate for small microcontroller implementations.However, only an implementation featuring the three M/S/U modes is useful for systems requiring virtualization.

ISA 提供的模块化允许仅以 M 或 M/U 为特征的实现,这最适合小型微控制器实现。但是,只有具有三种 M/S/U 模式的实现,对需要虚拟化的系统是有用的。

The ISA was designed from the ground-up to be classically virtualizable [18] by allowing to selectively trap accesses to virtual memory management control and status registers (CSRs) as well as timeout and mode change instructions from supervisor/user to machine mode.

ISA 从一开始就被设计为经典可虚拟化 [18] 的模型,允许选择性地捕获对虚拟内存管理控制和状态寄存器(CSR)的访问,以及超时(timeout)和从 supervisor/user 到 machine 模式的模式转换指令。

For instance, mstatus’s trap virtual memory (TVM) bit enables trapping of satp, the root page table pointer, while setting the trap sret (TSR) bit will cause the trap of the sret instruction used by supervisor to return to user mode. Furthermore, RISC-V provides fully precise exception handling, guaranteeing the ability to fully specify the instruction stream state at the time of an exception.

例如:

- mstatus 的 trap virtual memory (TVM) 位可以开启 satp(即,根页表指针,root page table page)的陷入(trapping),而设置 trap sret (TSR) 位将导致 supervisor 使用 sret 指令从 trap 返回到用户模式;

- 此外,RISC‑V 提供了完全精确的异常处理,保证了在发生异常时,具备能完全确定指令流状态(fully specify the instruction stream state)的能力。

The ISA simplicity coupled with its virtualization-friendly design allow the easy implementation of a hypervisor recurring to traditional techniques (e.g., full trap-and-emulate, shadow page tables) as well as the emulation of the hypervisor extension, described further ahead in this section, from machine mode. However, it is well-understood that such techniques incur large performance overheads.

将 ISA 的简单性与其对虚拟化友好的设计相结合,可以轻松实现与传统技术一样的 hypervisor(例如,完整的陷入和模拟、影子页表)以及 hypervisor 扩展的模拟,本节在前半部分将从机器模式开始对 RISC-V 的虚拟化做进一步的介绍。

但是,众所周知,此类技术会产生较大的性能开销。

Hypervisor 扩展(Hypervisor Extension)

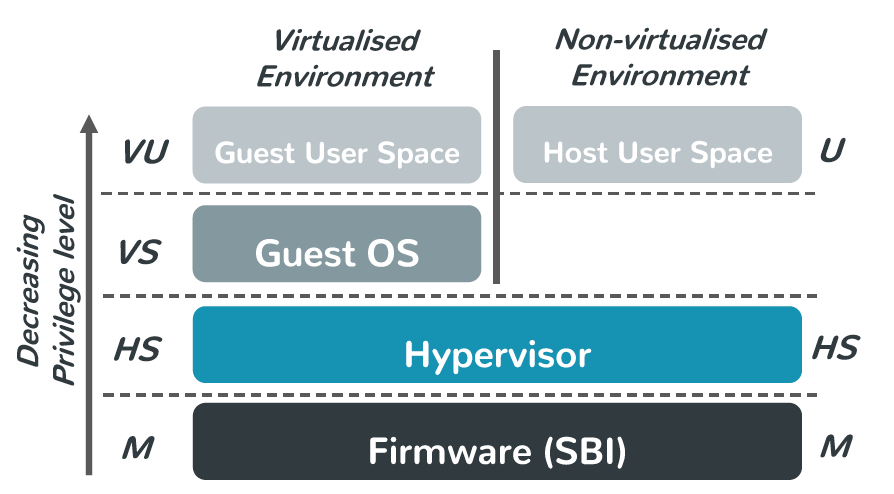

Like most other mainstream ISAs, the latest draft of the RISC-V privilege architecture specification offers hardware virtualization support, i.e., the optional hypervisor extension (“H”), to increase virtualization efficiency. As illustrated by Fig. 1, the H-extension modifies the supervisor mode to an hypervisor-extended supervisor mode (HS-mode), which similarly to Intel’s VT-x root mode, is orthogonal to the new virtual supervisor mode (VS-mode) and virtual user mode (VU-mode), and therefore can easily accommodate both bare-metal and hosted (a.k.a. type-1 and -2) as well as hybrid hypervisor architectures.

与大多数其他主流 ISA 一样,RISC-V 特权架构规范的最新草案提供了硬件虚拟化支持,即可选的 hypervisor 扩展(”H”),以提高虚拟化效率。如图 1 所示,H 扩展将 supervisor 模式修改为基于 hypervisor 扩展的(hypervisor-extended)supervisor 模式(HS‑mode),类似于 Intel 的 VT-x Root 模式,与新的虚拟 supervisor 模式(VS 模式)和虚拟 user 模式(VU 模式)正交,因此可以轻松适应裸机和托管(又名 type-1 和 type‑2)以及混合 hypervisor 架构。

Fig. 1: RISC-V privileged levels: machine (M), hypervisor-extended supervisor (HS), virtual supervisor (VS), and virtual user (VU).

图 1. RISC-V 的特权级别:machine (M) 级、hypervisor-extended supervisor (HS) 级、virtual supervisor (VS) 级和 virtual user (VU) 级。

Unavoidably, the extension also introduces two-stage address translations where the hypervisor controls the page tables mapping guest-physical to host-physical addresses. The virtualization mode is controlled by the implicit V bit. When V is set, either VU- or VS-mode are executing and 2nd stage translation is in effect. When V is low, the system may execute in M-, HS- or U- mode. The extension defines a few new hypervisor instructions and CSRs, as well as extends existing machine CSRs to control the guest virtual memory and execution.

不可避免地,该扩展还引入了两阶段地址翻译,其中 hypervisor 控制将 Guest 物理地址映射到 Host 物理地址的页表。虚拟化模式由隐含的 V 位控制。设置 V 时,VU 或 VS 模式正在执行,并且第二阶段翻译生效。当 V 为低电平时,系统可以在 M 模式、HS 模式 或 U 模式下执行。该扩展定义了一些新的 hypervisor 指令和 CSR,并扩展了现有的机器 CSR 以控制 Guest 虚拟内存和执行。

For example, the hstatus allows the hypervisor to track and control virtual machine exception behavior, hgatp points to the 2nd-stage root page table, and the hfence instructions allow the invalidation of any TLB entries related to guest translations.

例如,hstatus 允许 hypervisor 跟踪和控制虚拟机异常行为,hgatp 指向 2nd‑stage 根页表,hfence 指令允许与 Guest 地址翻译相关的任何 TLB 条目失效(invalidation)。

Additionally, it introduces a set of virtual supervisor CSRs which act as shadows for the original supervisor registers when the V bit is set. A hypervisor executing in HS-mode can directly access these registers to inspect the virtual machine state and easily perform context switches. The original supervisor registers which are not banked must be manually managed by the hypervisor.

此外,它还引入了一组虚拟 supervisor 的 CSR,当 V 位被设置时,它们充当原始管理器寄存器的影子。在 HS 模式下执行的 hypervisor 可以直接访问这些寄存器以检查虚拟机状态并轻松执行上下文切换。未存储的原始 supervisor 寄存器必须由 hypervisor 手动管理。

An innovative mechanism introduced with the H-extension is the hypervisor virtual machine load and store instructions. These instructions allow the hypervisor to directly access the guest virtual address space to inspect guest memory without explicitly mapping it in its own address space.

H 扩展引入的一种创新机制是 hypervisor 虚拟机加载和存储指令。这些指令允许 hypervisor 直接访问 Guest 虚拟地址空间以检查 Guest 内存,而无需将其显式映射到自己的地址空间中。

Furthermore, because these accesses are subject to the same permissions checks as normal guest access, it precludes against confused deputy attacks when, for example, accessing indirect hypercall arguments. This capability can be extended to user mode, by setting hstatus hypervisor user mode (HU) bit. This further simplifies the implementation of (i) type-2 hypervisors such as KVM [6], which hosts device backends in userland QEMU, or (ii) microkernel-based hypervisors such as seL4 [19], which implement virtual machine monitors (VMMs) as user-space applications.

此外,由于这些访问与普通 Guest 访问一样受到相同的权限检查,因此它可以防止混淆代理攻击(confused deputy attack),例如,间接访问 hypercall 调用的参数。通过设置 hstatus hypervisor user 模式的(HU)位,可以将此功能扩展到 user 模式。这进一步简化了:

- type-2 hypervisor 的实现,例如 KVM [6],它在用户级 QEMU 中托管设备后端;

- 基于微内核的 hypervisor 的实现,例如 seL4 [19],它实现虚拟机监视器(virtual machine monitor, VMM)作为用户空间应用程序。

With regard to interrupts, in RISC-V, there are three basic types: external, timer, and software (essentially used as IPIs). ss 关于中断,在 RISC‑V 中,有三种基本类型:

- 外部中断;

- 定时器中断;

- 软件中断(本质上用作 IPI)。

Each interrupt can be re-directed to one of the privileged modes by setting the bit for target interrupt/mode in a per-hart (hardware-thread, essentially a core in RISC-V terminology) interrupt pending bitmap, which might be directly driven by some hardware device or set by software. This bitmap is fully visible to M-mode through the mip CSR, while the S-mode has a filtered view of its interrupt status through sip.

通过在 per‑hart(硬件线程,hardware-thread,本质上是 RISC‑V 术语中的 core)中断挂起位图(interrupt pending bitmap)中设置目标中断/模式位,每个中断都可以被重定向到特权模式之一,这可能是由某些硬件设备直接驱动或由软件设置。此位图通过 mip CSR 对 M 模式完全可见,而 S 模式会通过 sip 将中断状态进行过滤(a filtered view)。

This concept was extended to the new virtual modes through the hvip, hip, and vsip CSRs. As further detailed in Section 4, in current RISC-V implementations, a hardware module called the CLINT (core-local interrupter) drives the timer and software interrupts, but only for machine mode.

这个概念通过 hvip、hip 和 vsip CSR 扩展到新的虚拟模式。如第 4 节中进一步详述的,在当前的 RISC‑V 实现中,称为 CLINT(核心本地中断器,core-local interruptr)的硬件模块驱动定时器和软件中断,但仅适用于机器模式。

Supervisor software must configure timer interrupts and issue IPIs via SBI, invoked through ecall (environment calls, i.e., system call) instructions. The firmware in M-mode is then expected to inject these interrupts through the interrupt bitmap in the supervisor. The same is true regarding VS interrupts as the hypervisor must itself service guest SBI requests and inject these interrupts through hvip while in the process invoking the machine-mode layer SBI.

Supervisor 软件必须配置定时器中断并通过 SBI 发出 IPI,通过 ecall(环境调用,即系统调用)指令调用。然后,M 模式下的固件被期望通过 hypervisor 中的中断位图注入这些中断。对于 VS 中断也是如此,因为 hypervisor 本身必须服务 Guest 的 SBI 请求,并在调用 M 模式层 SBI 的过程中通过 hvip 注入这些中断。

When the interrupt is triggered for the current hart, the process is inversed: (i) the interrupt traps to machine software, which must then (ii) inject the interrupt in HS-mode through the interrupt pending bitmap, and then (iii) inject it in VS mode by setting the corresponding hvip bit.

当前 hart 触发中断时,中断处理的过程是相反的:

- 首先,中断陷入到 M 模式的软件中;

- 然后,必须通过中断挂起位图(interrupt pending bitmap)将中断注入到 HS 模式;

- 最后,通过设置相应的 hvip 位在 VS 模式下注入中断。

As for external interrupts, these are driven by the platform-level interrupt controller (PLIC) targeting both M and HS modes. The hypervisor extensions specifies a guest external interrupt mechanism which allows an external interrupt controller to directly drive the VS external interrupt pending bit. This allows an interrupt to be directly forward to a virtual machine without hypervisor intervention (albeit in an hypervisor controlled manner).

至于外部中断,它们由面向 M 和 HS 模式的平台级中断控制器(PLIC)驱动。hypervisor 扩展指定了 Guest 外部中断机制,允许外部中断控制器直接驱动 VS 外部中断挂起位(VS external interrupt pending bit)。这允许中断直接转发到虚拟机而无需 hypervisor 干预(尽管是以 hypervisor 控制的方式)。

However, this feature needs to be supported by the external interrupt controller. Unfortunately, the PLIC is not yet virtualization-aware. A hypervisor must fully trap-and-emulate PLIC accesses by the guest and manually drive the VS external interrupt pending bit in hvip. The sheer number of traps involved in these processes is bound to impact interrupt latency, jitter, and, depending on an OS tick frequency, overall performance. For these reasons, interrupt virtualization support is one of the most pressing open-issues in RISC-V virtualization. In section 4, we describe our approach to address this issue.

但是,此功能需要外部中断控制器支持。不幸的是,PLIC 还没有支持虚拟化。hypervisor 必须完全捕获并模拟 Guest 对 PLIC 的访问,并手动驱动 hvip 中的 VS 外部中断挂起位。这些进程中涉及的大量陷入势必会影响中断延迟、抖动,并且取决于操作系统的 tick 频率,还会影响整体性能。由于这些原因,中断虚拟化支持是 RISC‑V 虚拟化中最紧迫的开放问题之一。在第 4 节中,我们描述了我们解决此问题的方法。

The hypervisor extension also augments the trap encoding scheme with multiple exceptions to support VS execution. For instance, it adds guest-specific page faults exceptions for when translations at the second stage MMU fail, as well as VS-level ecalls which equate to hypercalls.

hypervisor 扩展还增加了带有多个异常的陷入编码方案(trap encoding scheme),以支持 VS 执行。例如,当第二阶段 MMU 的翻译失败时,它添加了特定于 Guest 的页面错误异常(page fault exception),以及等同于 hypercall 的 VS 级调用(ecall)。

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the specification is tailored to seamlessly support nested virtualization; however, nested virtualization is out-of-scope of this article.

最后,值得一提的是,该规范是为无缝支持嵌套虚拟化而量身定制的;但是,嵌套虚拟化超出了本文的范围。

Rocket Core 的 hypervisor 扩展(ROCKET CORE HYPERVISOR EXTENSION)

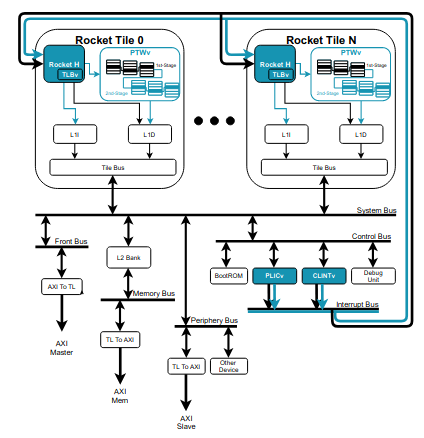

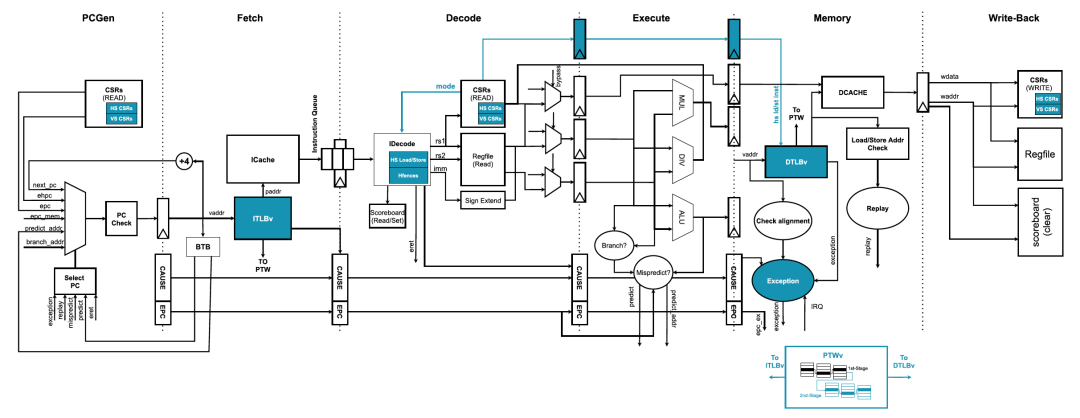

We have implemented the RISC-V hypervisor extension in the open-source Rocket core, a modern 5-stage, in-order, highly configurable core, part of the Rocket chip SoC generator [16] and written in the novel Chisel hardware construction language [20] (Figure 2). Despite being possible to configure this core according to the 32- or 64-bit variants of the ISA (RV32 or RV64, respectively), our implementation currently only supports the latter. The extension can be easily enabled by adding a WithHyp configuration fragment in a typical Rocket chip configuration.

我们在开源 Rocket 内核中实现了 RISC‑V hypervisor 扩展 (3),这是一个现代的 5 级(5-stage)、有序(in-order)、高度可配置(highly configurable core)的内核,是 Rocket 芯片 SoC 生成器 [16] 的一部分,并以新颖的 Chisel 硬件结构编写语言 [20] 编写(图 2)。尽管可以根据 ISA 的 32 位或 64 位变体(分别为 RV32 或 RV64)配置此内核,但我们的实现目前仅支持后者。通过在典型的 Rocket 芯片配置中添加 WithHyp 配置片段,可以轻松启用该扩展。

Fig. 2: Rocket chip diagram. H-extension and interrupt virtualization enhancements (CLINTv and PLICv) highlighted in blue. Adapted from [16].

图 2. Rocket 芯片示意图。H 扩展和中断虚拟化增强(CLINTv 和 PLICv)以蓝色突出显示。改编自 [16]。

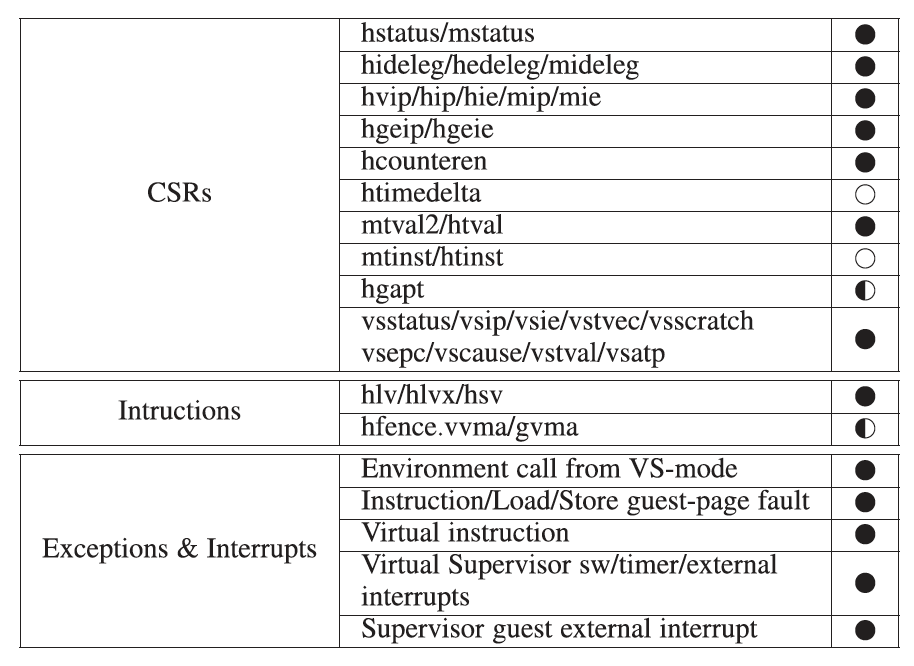

Hypervisor 的 CSR 和指令(Hypervisor CSRs and Instructions)

The bulk of our H-extension implementation in the Rocket core revolves around the CSR module which implements most of the privilege architecture logic: exception triggering and delegation, mode changes, privilege instruction and CSRs, their accesses, and respective permission checks. These mechanisms were straightforward to implement, as very similar ones already exist for other privilege modes. Although most of the new CSRs and respective functionality mandated by the specification were implemented, we have left out some optional features.

我们在 Rocket 核心中的大部分 H 扩展实现都围绕着 CSR 模块,该模块实现了大部分特权架构逻辑:异常触发(exception triggering)和委托(delegation)、模式更改(mode changes)、特权指令(privilege instruction)和对 CSR 的访问,以及各自的权限检查。这些机制很容易实现,因为其他特权模式已经存在非常相似的机制。虽然大多数新的 CSR 和规范强制要求的相应功能都已实现,但我们省略了一些可选功能。

Specifically: 1) htimedelta is a register that contains the difference between the value obtained by a guest when reading the time register and the actual time value. We expect this register to be emulated by the firmware running in M-mode as it is the only mode allowed to access time (see CLINT background in section 4.1); 2) htinst and mtinst are hardwired to zero. These registers expose a trapping instruction in an easy and pre-decoded form so that the hypervisor can quickly handle the trap while avoiding reading the actual guest instruction and polluting the data cache; 3) hgatp is the hypervisor’s 2nd-stage root page-table pointer register. Besides the pointer it allows to specify a translation mode (essentially, page-table formats and address space size) and the VMID (virtual machine IDs, akin to 1st-stage ASIDs). The current implementation does not support VMIDs and only allows for the Sv39x4translation mode; 4) the hfence instructions, which are the hypervisor TLB synchronization or invalidation instructions, always invalidate the full TLB structures. However, the specification allows to provide specific virtual addresses and/or a VMID to selectively invalidate TLB entries.

具体来说:

htimedelta 是一个寄存器,包含 Guest 在读取时间寄存器时获得的值与实际时间值之间的差值。我们希望这个寄存器能够被运行在 M 模式下的固件所模拟,因为 M 模式是唯一允许访问时间的模式(参见第 4.1 节中的 CLINT 背景);

htinst 和 mtinst 硬连线为零(hardwired to zero)。这些寄存器以简单的、预解码的形式暴露了一个陷入指令,以便 hypervisor 可以快速处理陷入,同时避免读取实际的 Guest 指令或污染数据缓存;

hgatp 是 hypervisor 的第二阶段根页表指针寄存器。除了指针之外,它还允许指定翻译模式(本质上是页表格式和地址空间大小)和 VMID(虚拟机 ID,类似于第一阶段的 ASID)。当前实现不支持 VMID,只允许 Sv39x4 翻译模式;

hfence 指令,即 hypervisor TLB 同步或失效指令(TLB synchronization or invalidation instruction),总是使整个 TLB 结构失效。但是,该规范允许提供特定的虚拟地址 和/或 VMID 以选择性地使 TLB 条目无效。

Nevertheless, all the mandatory H-extension features are implemented and, therefore, our implementation is fully compliant with the RISC-V H-extension specification. Table 1 summarizes all the included and missing features.

尽管如此,所有强制性的 H 扩展功能都已实现,因此,我们的实现完全符合 RISC‑V H 扩展规范。表 1 总结了所有包含和缺失的功能。图 3 强调了 Rocket 核心功能块的主要架构变化。

TABLE 1: Current state of Hypervisor Extension features implemented in the Rocket core: fully-implemented.

表 1. Rocket 核心中实现的 Hypervisor 扩展功能的当前状态:“黑色实心”代表完全实现;“黑白相间”代表部分实现;“白色实心”代表未实现。

Fig. 3: Rocket core microarchitecture overview featuring the H-extension. Major architectural changes to the Rocket core functional blocks (e.g., Decoder, PTW, TLBs, and CSRs) are highlighted in blue. Adapted from 3.

图 3. 具有 H 扩展的 Rocket 核心微体系结构概览。Rocket 核心功能块(例如,解码器、PTW、TLB 和 CSR)的主要架构更改以蓝色突出显示。改编自 [3]。

两阶段地址翻译(Two-stage Address Translation)

The next largest effort focused on the MMU structures, specifically the page table walker (PTW) and translation-lookaside buffer (TLB), in particular, to add to support for the 2nd-stage translation. The implementation only supports the Bare translation mode (i.e., no translation) and the Sv39x4, which defines a specific page table size and topology which results in guest-physical addresses with a maximum width of 41-bits.

下一个最大的努力集中在在 MMU 结构上,特别是页表遍历器(page table walker, PTW)和翻译后备缓冲区(translation-lookaside buffer, TLB),以添加对第二阶段翻译的支持。该实现仅支持裸翻译模式(即不翻译)和 Sv39x4。Sv39x4 定义了特定的页表大小和拓扑,这导致 Guest 物理地址的最大宽度为 41 位。

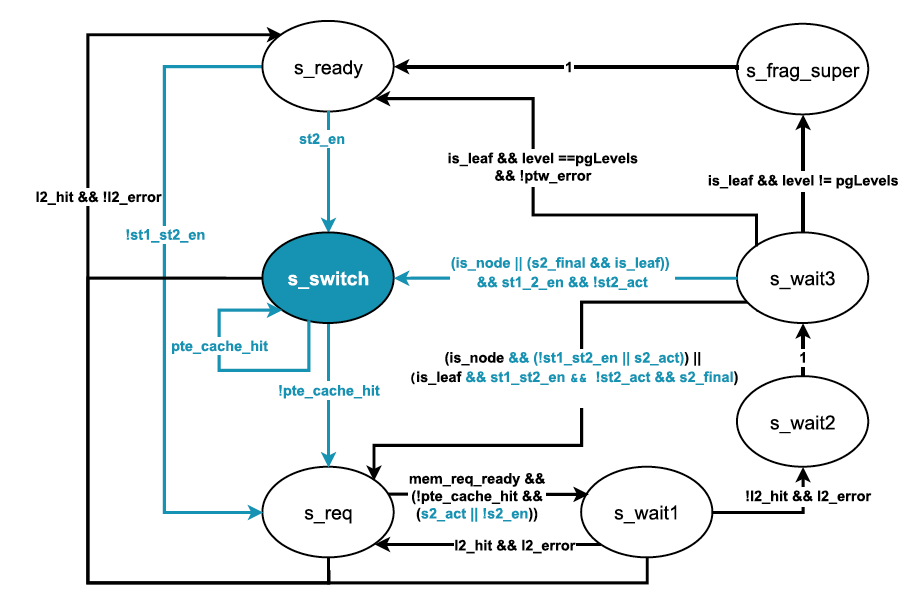

The modification to the PTW extends the module’s state-machine so that it switches to perform 2nd-stage translation at each level of the 1st translation stage (Figure 4). At each step it merges the results of both stages. When a guest leaf PTE (page table entry) is reached, it performs a final translation of the targeted guest-physical address.

对 PTW 的修改扩展了模块的状态机,使得它在第一阶段翻译的每一级都会切换去执行第二阶段翻译(图 4)。在每一步中,它都合并了两个阶段的结果。当到达 Guest 页表条目 PTE(page table entry)时,它对目标 Guest 物理地址执行最终的翻译。

Fig. 4: PTW state machine featuring the two-stage translation. Modifications to the state machine, including a new state(s switch) to switch the translation between the two stages (e.g., change the root page-table pointer), are highlighted in blue.

图 4. PTW 状态机具有两阶段翻译功能。对状态机的修改,包括新状态(s switch)在两个阶段之间切换翻译(例如,更改根页表指针),以蓝色突出显示。

This proved to be one of the trickiest mechanisms to implement, given the large number of corner cases that arise when combining different page sizes at each level and of exceptions that might occur at each step of the process. TLB entries were also extended to store both the direct guest-virtual to host-physical address as well as the resulting guest-physical address of the translation. This is needed because even for a valid cached 2-stage translation, later accesses might violate one of the RWX permissions, and the specification mandates that the guest-physical address must be reported in htval when the resulting exception is triggered.

这被证明是最棘手的实现机制之一,因为会有非常多的特殊情况需要考虑到,包括要考虑在每一级组合不同的页面大小,在过程中的每个步骤中可能发生的异常处理。

TLB 条目也被扩展去同时存储直接的 Guest-虚拟地址到 Host-物理地址,以及转换后的 Guest-物理地址。这是必要的,因为即使对于有效的缓存的 2 阶段翻译,以后的访问可能会违反 RWX 权限之一,并且规范要求当结果中的异常被触发时,Guest 物理地址必须在 htval 中报告。

Note that the implementation does not support VMID TLB entry tagging. We have decided to neglect this optional feature for two mains reasons. Firstly, at the time of this witting, the Rocket core did not even support ASIDs. Secondly, static partitioning hypervisors (our main use case) do not use it at all. A different hypervisor must invalidate these structures at each context-switch. As such, the implemented support for hfence instructions ignores the VMID argument. Furthermore, they invalidate all cached TLB or walk-cache entries used in guest translation, despite it specifying a virtual address argument, or being targeted at only the first stage (hfence.hvma) or both stages (hfence.gvma).

注意,该实现不支持 VMID TLB 条目标记(VMID TLB entry tagging)。出于两个主要原因,我们决定忽略此可选功能:

- 首先,在进行这项工作时,Rocket 核心甚至不支持 ASID;

- 其次,静态分区 hypervisor(我们的主要用途案例)并不需要使用它。不同的 hypervisor 必须在每次上下文切换时使这些结构失效。因此,实施对 hfence 指令的支持会忽略 VMID 参数。此外,尽管它指定了一个虚拟地址参数,或仅针对第一阶段(hfence.hvma)或两个阶段(hfence.gvma),它使所有用于 Guest 翻译的缓存的 TLB 或 walk‑cache 条目失效。

To this end, an extra bit was added to TLB entries to differentiate between the hypervisor and virtual-supervisor translations. Finally, we have not implemented any optimizations such as dedicated 2nd-stage TLBs as many modern comparable processors do, which still leaves room for important optimizations.

为此,我们在 TLB 条目添加了一个额外的位,以区分 hypervisor 和虚拟 supervisor 翻译。最后,我们还没有实现任何优化,就像许多类似的现代处理器一样,使用专用的第二阶段 TLB,这将是未来需要重要优化的方向。

Hypervisor 虚拟机加载和存储指令(Hypervisor Virtual-Machine Load and Store Instructions)

Despite most of the implementation being straightforward, because it mainly involved replicating or extending existing or very similar functionality and mechanisms, the most invasive implemented feature was the support for hypervisor virtual-machine load and store instructions. This is because, although RISC-V already provided mechanisms for a privilege level to perform memory accesses subject to the same translation and restrictions of a lower privilege (such as by setting the modify privilege - MPRV - bit in mstatus), these sync the pipeline instruction stream which results in the actual access permission modifications being associated with the overall hart state and not tagged to a specific instruction.

尽管大多数实现都很直接,因为它主要涉及复制或扩展现有的或非常相似的功能和机制,但最具侵入性的实现功能是支持 hypervisor 虚拟机加载和存储指令。

这是因为,虽然 RISC‑V 已经提供特权级别的机制,让一个特权级别在执行内存访问时,得到更低特权的相同翻译和限制(例如通过设置修改权限 ‑ mstatus 中的 MPRV 位)。这些导致实际访问权限修改的同步流水线指令流将与整体的 hart 状态相关联,并且不会被标记为特别的指令。

As such, we added dedicated signals that needed to be propagated throughout the pipeline starting from the decode stage, going through the L1 data cache up to the data TLB to signal the memory access originates from a hypervisor load/store. If this signal is set, the TLB will ignore the current access privilege (either HS or HU), and fetch the translation and perform the privilege checks as the access was coming from a virtual machine (VS or VU). Similar signals already existed for the fence instructions.

因此,我们添加了专门的信号,需要从解码阶段开始在整个流水线上传递,通过 L1 数据缓存直到数据 TLB,以示内存访问源自 hypervisor 加载/存储指令。如果这个信号被设置,TLB 将忽略当前的访问权限(HS 或 HU),而是去翻译并执行权限检查,因为访问来自虚拟机(VS 或 VU)。

类似的信号已经存在于栅栏指令(fence instruction)中。

其他修改(Other modifications)

The Rocket chip generators truncate physical address width signals to the maximum needed for the configured physical address space. Thus, another issue we faced was the need to adapt the bit-width of some buses and register assumed to be carrying physical addresses to support guest-physical addresses, essentially virtual addresses.

Rocket 芯片生成器将物理地址宽度信号截断为配置的物理地址空间所需的最大值。因此,我们面临的另一个问题是需要调整某些总线和寄存器的位宽,这些总线和寄存器假定承载的是物理地址,以支持 Guest 物理地址,但其本质上是虚拟地址。

Finally, we also needed to slightly modify the main core pipeline to correctly forward virtual exceptions, including the new virtual instruction exception, to the CSR module along with other hypervisor-targeted information such as faulting guest-physical addresses to set the htval/mtval registers.

最后,我们还需要稍微修改主核心流水线,以正确地将虚拟异常(包括新的虚拟指令异常)连同其他针对 hypervisor 的信息转发到 CSR 模块(例如为 Guest 物理地址报错(faulting guest-physical addresses)来设置 htval/mtval 寄存器)。

中断虚拟化的增强(INTERRUPT VIRTUALIZATION ENHANCEMENTS)

As explained in the previous sections, RISC-V support for virtualization still only focuses on CPU virtualization. Therefore, as illustrated in Figure 2, we have also extended other Rocket chip components, namely the PLIC and the CLINT, to tackle some of the previously identified drawbacks regarding interrupt virtualization.

如前几节所述,RISC‑V 对虚拟化的支持仍然只关注 CPU 虚拟化。因此,如图 2 所示,我们还扩展了其他 Rocket 芯片组件,即 PLIC 和 CLINT,以解决之前发现的有关中断虚拟化的一些缺陷。

定时器虚拟化(Timer virtualization)

CLINT 背景(CLINT background)

CLINT is the core-level interrupt controller responsible for maintaining machine-level software and timer interrupts in the majority of RISC-V systems. To inject software interrupts (IPIs in RISC-V lingo) in M-mode, the CLINT facilitates a memory-mapped register, denoted msip, where each register is directly connected to a running CPU.

CLINT 是核心级(core-level)中断控制器,负责在大多数 RISC‑V 系统中维护 machine 级的软件和定时器中断。为了在 M 模式下注入软件中断(RISC‑V 术语中的 IPI),CLINT 提供了一个内存映射的寄存器(memory-mapped register),表示为 msip,其中每个寄存器直接连接到正在运行的 CPU。

Moreover, the CLINT also implements the RISC-V timer M-mode specification, more specifically the mtime and mtimecmp memory-mapped control registers. mtime is a free-running counter and a machine timer interrupt is triggered when its value is greater than the one programmed in mtimecmp. There is also a read-only time CSR accessible to all privilege modes, which is not supposed to be implemented but converted to a MMIO access of mtime or emulated by firmware.

此外,CLINT 还实现了 RISC‑V 定时器 M 模式规范,更具体地说,是 mtime 和 mtimecmp 内存映射控制寄存器。mtime 是一个自由运行的计数器,当它的值大于在 mtimecmp 中编程的值时,会触发 machine 定时器中断。还有一个所有特权模式都可以访问的只读时间 CSR,没有必要去实现它,应该转换为 mtime 的 MMIO 访问或由固件模拟。

Thus, M-mode software implementing the SBI interface (e.g., OpenSBI) must facilitate timer services to lower privileges via ecalls, by multiplexing logical timers onto the M-mode physical timer.

因此,M 模式下软件所实现的 SBI 接口(例如 OpenSBI)必须通过 ecall,即通过将逻辑计时器多路复用到 M 模式的物理计时器上,来为更低的特权级提供定时器服务。

CLINT 虚拟化开销(CLINT virtualization overhead)

Naturally, this mechanism introduces additional burdens and impacts the overall system performance for HS-mode and VS-Mode execution, especially in high-frequency tick OSes. As explained in section 2, a single S-mode timer event involves several M-mode traps, i.e., first to set up the timer and then to inject the interrupt in S-mode.

自然地,这种机制引入了额外的负担并影响了 HS 模式和 VS 模式执行的整体系统性能,尤其是在高频 tick 操作系统中。如第 2 节所述,单个 S 模式定时器事件涉及多个 M 模式陷入,即首先设置定时器,然后在 S 模式中注入中断。

This issue is further aggravated in virtualized environments as it adds extra HS-mode traps. The simplest solution to mitigate this problem encompasses providing multiple independent hardware timers directly available to the lower privilege levels, HS and VS, through new registers analogous to the M-mode timer registers. This approach is followed in other well-established computing architectures. For instance, the Armv8-A architecture has separate timer registers across all privilege levels and security states.

这个问题在虚拟化环境中更加严重,因为它增加了额外的 HS 模式陷入。缓解此问题的最简单解决方案包括通过类似于 M 模式定时器寄存器的新寄存器,来提供多个独立的硬件定时器,这些定时器可直接用于更低特权级别 HS 和 VS。这种方法在其他成熟的计算架构中也采用了。例如,Armv8‑A 架构具有跨所有特权级别和安全状态的单独定时器寄存器。

CLINT 虚拟化扩展(CLINT virtualization extensions)

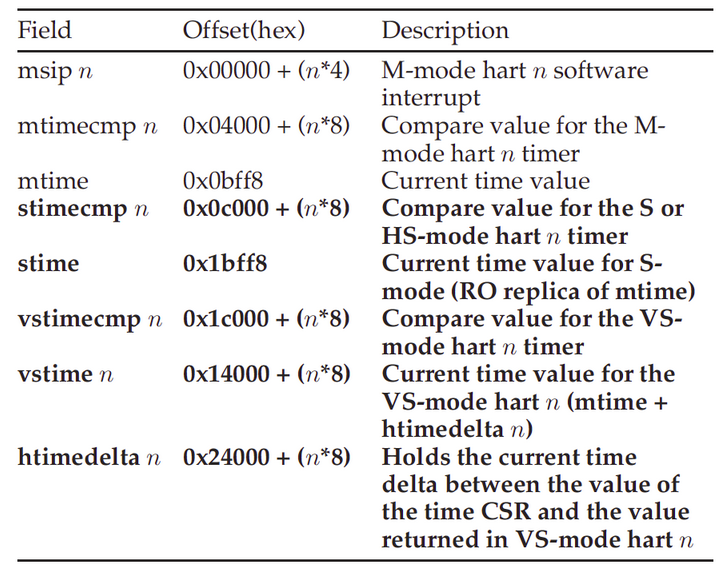

TABLE 2: CLINT memory map. In bold, the new HS and VS timer registers.

表 2. CLINT 内存映射。以粗体显示的新 HS 和 VS 定时器寄存器。

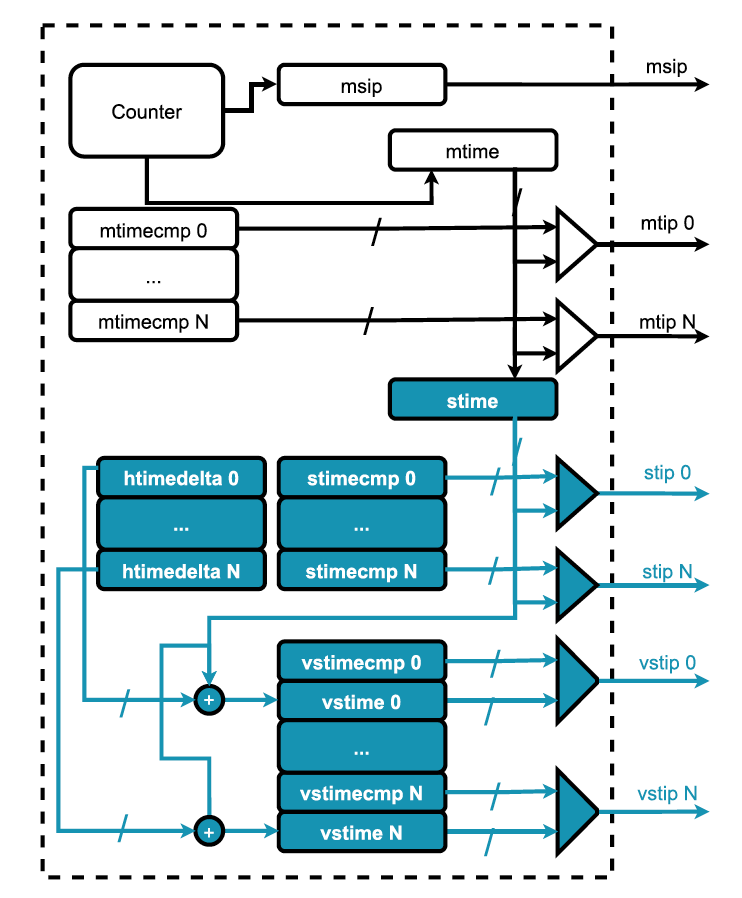

As detailed in Table 2, we added read-only stime and vstime, as well as read/write stimecmp and vstimecmp memory-mapped registers to the CLINT. Furthermore, we implemented a memory-mapped version of the htimedelta CSR, which defines a drift of time as viewed from VS- or VU-mode perspectives. In our implementation (see Figure 5), htimedelta will be reflected in the value of vstime, by adding it to the value of mtime.

如表 2 所述,我们向 CLINT 添加了只读 stime 和 vstime,以及读/写 stimecmp 和 vstimecmp 内存映射寄存器。此外,我们实现了 htimedelta CSR 的内存映射版本,它定义了从 VS 或 VU 模式的角度来看的时间漂移。在我们的实现中(参见图 5),htimedelta 将反映在 vstime 的值中,方法是将其添加到 mtime 的值中。

Fig. 5: CLINT microarchitecture with virtualization enhancements. Architectural changes to include hardware support for S and VS mode timers are highlighted in blue.

图 5. 具有虚拟化增强功能的 CLINT 微架构。包含对 S 和 VS 模式计时器的硬件支持的架构更改以蓝色突出显示。

Adopting such approach would enable S-mode software to directly interact with its timer and receive interrupts without firmware mediation. In CLINT implementations each type of timer registers are mapped onto separate pages. However, hart replicas of the same register are packed contiguously in the same page. As such, with this approach, the hypervisor still needs to mediate VS- register access as it cannot isolate VS registers of each individual virtual hart (or vhart) using virtual memory.

采用这种方法将使 S 模式软件能够直接与其定时器交互并接收中断,而无需固件介入。在 CLINT 实现中,每种类型的定时器寄存器都映射到单独的页面上。但是,同一寄存器的 hart 副本被连续打包在同一页中。因此,使用这种方法,hypervisor 仍然需要介入 VS 寄存器访问,因为它无法使用虚拟内存隔离每个单独的虚拟 hart(或 vhart)的 VS 寄存器。

Nevertheless, traps from HS- to M-mode are no longer required, and when the HS and VS timer expires, the interrupt pending bit of the respective privilege level is directly set.

然而,这种方法不再需要从 HS 到 M 模式的陷入,并且当 HS 和 VS 定时器到期时,可以直接设置相应特权级别的中断挂起位。

CLINT 和其他提案对比(CLINTv vs Other proposals)

Concurrently to our work, there have been some proposals discussed among the community to include dedicated timer CSRs for HS and VS modes. The latest one which is officially under con-sideration, at a high-level, is very similar to our implemen-tation. However, there are differences with regard to: first, it does not include stime and vstime registers but only the respective timer compares; second, and more important, we add the new timer registers as memory-mapped IO (MMIO) in the CLINT, and not as CSRs. The rationale behind our decision is based on the fact that the RISC-V specification states that the original M-mode timer registers are memory-mapped, due to the need to share them between all harts as well as due to power and clock domain crossing concerns.

在我们的工作的同时,社区讨论了一些提案,包括为 HS 和 VS 模式提供的专用计时器 CSR。最新的一个正在被正式地考察的提案,总的来说,与我们的实现非常相似。但是,在以下方面存在差异:

- 首先,它不包括 stime 和 vstime 寄存器,而只有各自的计时器比较;

- 其次,更重要的是,我们将新的定时器寄存器添加为 CLINT 中的内存映射 IO (MMIO),而不是 CSR。

我们最终提出 CLINT 方案的理由是基于这样的事实,RISC‑V 规范声明了原始 M 模式定时器寄存器是内存映射的,因为需要在所有 hart 之间共享它们以及考虑到电源和时钟域的交叉情况。

As the new timers still directly depend on the original mtime source value, we believe its simpler to implement them as MMIO, centralizing all the timer logic. Otherwise, every hart would have to con-tinuously be aware of the global mtime value, possibly through a dedicated bus. Alternatively, it would be possi-ble to provide the new registers, as well as htimedelta, through the CSR interface following the same approach as the one used for time, i.e., by converting the CSR accesses to memory accesses. This approach would, however, in our view, add unnecessary complexity to the pipeline as supervisor software can always be informed of the platform’s CLINT physical address through standard methods (e.g., device tree).

由于新的定时器仍然直接依赖于原始的 mtime 数值,我们认为将它们实现为 MMIO 更简单,可以把所有定时器的逻辑集中起来。否则,每个 hart 都必须不断地去同步全局的 mtime 值,可能会通过专用总线。或者,可以提供新的寄存器以及 htimedelta,像用于 time 的方法一样通过 CSR 的接口来访问,即将 CSR 访问转换为内存访问。

然而,在我们看来,这种方法会给流水线增加不必要的复杂性,因为 supervisor 软件总是可以通过标准方法(例如,设备树)获知平台的 CLINT 物理地址。

PLIC 虚拟化(PLIC Virtualization)

PLIC 背景(PLIC Background)

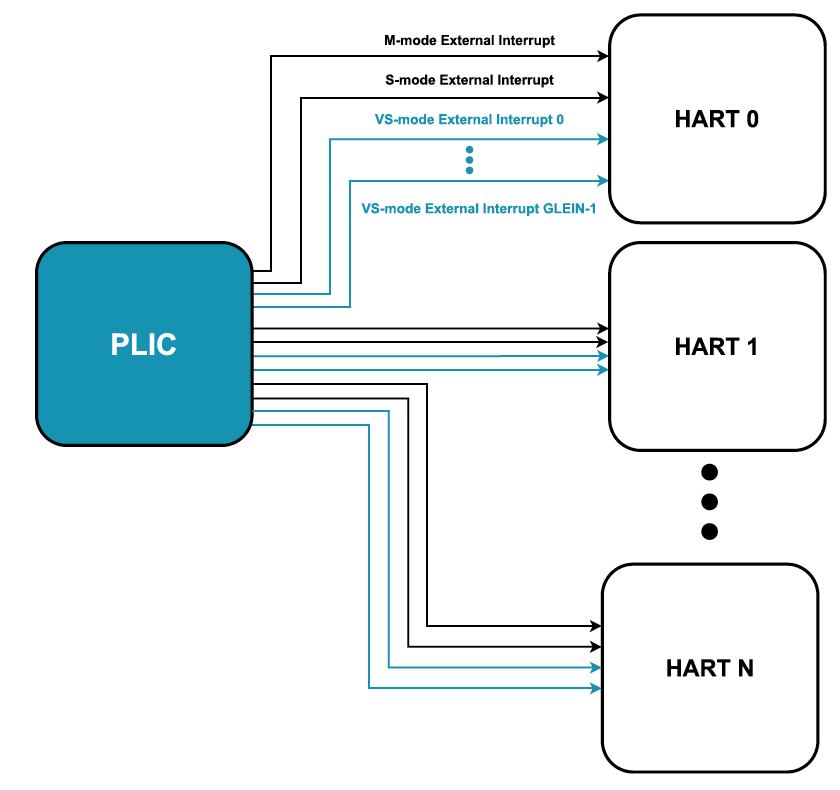

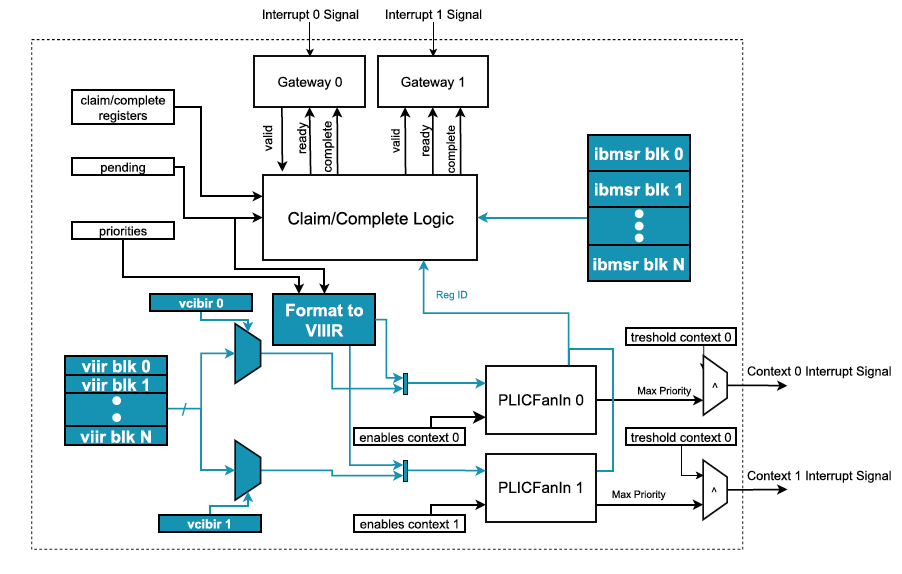

The PLIC is the external interrupt controller used in most current RISC-V systems. The PLIC is capable of multiplexing multiple devices interrupts to one or more hart contexts. More specifically, up to 1023 devices interrupt lines can be connected to the PLIC, each with its configurable priority. PLIC contexts represent a set of registers and external interrupts lines, each targeting a specific privilege level within a given hart (see Fig. 6). Each line will drive the corresponding privilege bit in the hart global external interrupt pending bitmap. Part of each context, the PLIC provides registers for interrupt enabling as well as for interrupt handling: upon entry on an interrupt handler, software reads a context claim register which returns the interrupt ID that triggered the interrupt.

PLIC 是当前大多数 RISC‑V 系统中使用的外部中断控制器。PLIC 能够将多个设备中断多路复用到一个或多个 hart 上下文。更具体地说,最多可以将 1023 条设备中断线连接到 PLIC,每条中断线都有其可配置的优先级。PLIC 上下文代表一组寄存器和外部中断线,每个都针对给定 hart 中的特定特权级别(见图 6)。每一行都会驱动 hart 全局外部中断挂起位图中对应的特权位。作为每个上下文的一部分,PLIC 提供用于中断启用和中断处理的寄存器:在进入中断处理程序时,软件读取上下文声明寄存器(context claim register),该寄存器返回触发中断的中断 ID。

To complete the interrupt handling process, the hart must write back to the complete register the retrieved interrupt ID. The claimed interrupt will not be re-triggered until the interrupt during this process. Beyond that, PLIC also supports context interrupt masking through the threshold regis-ter, i.e., interrupts with priority lower than the threshold value are not delivered to the context. Importantly, each set of claim/complete/threshold registers is mapped onto a different physical memory page.

为了完成中断处理过程,hart 必须将检索到的中断 ID 写回到完整的寄存器中。在此过程中,被声明(claimed)的中断不会重复触发,直到中断真正发生。除此之外,PLIC 还支持通过阈值寄存器(threshold register)进行上下文中断屏蔽,即优先级低于阈值的中断不会传递到上下文。重要的是,每组声明(claim)/完成(complete)/阈值(threshold)寄存器都映射到不同的物理内存页面。

PLIC 虚拟化开销(PLIC Virtualization Overhead)

Currently, only M-mode and S-mode contexts are supported (grey lines in Fig. 6), meaning the PLIC specification does not provide additional interrupt virtualization support. The hypervisor is then responsible for emulating PLIC control registers accesses and fully managing interrupt injection into VS-mode. Emulating PLIC interrupt configuration registers, such as enable and priority registers, may not be critical as it is often a one-time-only operation performed during OS initialization.

目前,仅 M 模式和 S 模式的上下文(图 6 中的灰线)被 PLIC 支持,这意味着 PLIC 规范不提供额外的中断虚拟化支持。然后 hypervisor 负责模拟 PLIC 控制寄存器访问并全面管理中断注入 VS 模式。模拟 PLIC 中断配置寄存器(例如启用和优先级寄存器)可能并不重要,因为它通常是在 OS 初始化期间执行的一次性操作。

Fig. 6: High-level virtualization-aware PLIC logic.

图 6. 宏观角度上虚拟化可感知的 PLIC 逻辑设计。

However, the same does not apply to the claim/complete registers, which must be accessed before and after every interrupt handler. For physical interrupts directly assigned to guests, this is further aggravated, since it incurs in the extra trap to the hypervisor to receive the actual interrupt before injecting it in the virtual PLIC. These additional mode-crosses causes a drastic increase in the interrupt latency and might seriously impact overall system perfor-mance, especially for real-time systems that rely on low and deterministic latencies.

但是,这不适用于声明/完成寄存器,必须在每个中断处理程序之前和之后访问它们。对于直接分配给 Guest 的物理中断,这种情况会更加严重,因为它会在 hypervisor 中产生额外的陷入,即需要在将中断注入虚拟 PLIC 之前,先陷入 hypervisor 去实际地接收中断。这些额外的模式交叉导致中断延迟急剧增加,并可能严重影响整体系统性能,尤其是对于依赖低延迟和确定延迟的实时系统。

PLIC 虚拟化增强功能(PLIC Virtualization Enhancements)

Based on the aforementioned premises, we propose a virtualization extension to the PLIC specification 006 that could significantly improve the system’s performance and latency by leveraging the guest external interrupt feature of the RISC-V hypervisor exten-sion (see Section 2).

基于上述前提,我们提出了 PLIC 规范的虚拟化扩展 (4),它可以通过利用 RISC‑V hypervisor 扩展的 Guest 外部中断功能显著地改善系统的性能和延迟(参见第 2 节)。

We had four main requirements: (i) allow direct assignment and injection of physical interrupts to the active VS-mode hart, i.e., without hypervisor intervention; (ii) minimize traps to the hypervisor, in particular, by eliminating traps on claim/complete register access; (iii) allow a mix of purely virtual and physical interrupts for a given VM; and (iv) a minimal design with a limited amount of additional hardware cost and low overall complexity.

我们有四个主要需求:

- 允许将物理中断直接分配和注入到活跃的 VS 模式 hart,即,无需 hypervisor 干预;

- 最大限度地减少对 hypervisor 的陷入,特别是消除对声明/完成寄存器(claim/complete register)访问的陷入;

- 允许为特定 VM 混合使用纯虚拟的和物理的中断;

- 有限的额外硬件成本和整体的低复杂度的最小设计。

We started by adding GEILEN VS-mode contexts to every hart. GEILEN is a hypervisor specification “macro” that defines the maximum (up to 64) available VS external interrupt contexts that can be simultaneously active for a hart, in a given implementation. This is a configurable parameter in our implementation. The context for the currently executing vhart is selected through the VGEIN field in the hstatus CSR. Fig. 6 highlights, in blue, the external interrupt lines associated with VS contexts that directly drive the hart’s VS mode external interrupt pending bits.

我们首先将 GEILEN VS 模式上下文添加到每个 hart。GEILEN 是一个 hypervisor 规范“宏”(”macro”),它定义了在给定实现中可以为一个 hart 同时激活可用的 VS 外部中断上下文的最大数目(上限为 64 个)。这是我们实现中的可配置参数。当前执行的 vhart 的上下文是通过 hstatus CSR 中的 VGEIN 字段选择的。图 6 以蓝色突出显示了与 VS 上下文相关的外部中断线,这些中断线直接驱动 hart 的 VS 模式外部中断挂起位。

With additional virtual contexts and independent context’s claim/complete regis-ter pair available on separate pages, the hypervisor can allow direct guest access to claim/complete registers by map-ping them in the guests’ physical address space, mitigating the need to trap-and-emulate such registers. However, access to configuration registers such as priority and enable registers are still trapped since these registers are not often accessed and are not in the critical path of interrupt han-dling.

通过在单独的页面上提供额外的虚拟上下文和独立上下文的声明/完成寄存器对,hypervisor 可以通过将它们映射到 Guest 的物理地址空间中来允许 Guest 直接访问声明/完整寄存器,从而减少陷入和模拟此类寄存器的需要。然而,对诸如优先级和使能寄存器等配置寄存器的访问仍然需要陷入,因为这些寄存器不会被经常访问并且不在中断处理的关键路径中。

A hypervisor might assign physical interrupts to a guest as follows. When a guest sets configurations register fields for a given interrupt, a hypervisor commits it to hardware in the vhart’s context if the interrupt was assigned to its VM. Otherwise, it might save it in memory structures if it corresponds to an existing virtual interrupt fully managed by the hypervisor.

hypervisor 可能会按如下方式将物理中断分配给 Guest。当 Guest 为给定中断设置配置寄存器字段时,如果将中断分配给其 VM,则 hypervisor 将其提交到 vhart 上下文中的硬件。否则,如果它对应于由 hypervisor 完全管理的已有的虚拟中断,它可能会将其保存在内存结构中。

PLICv 纯虚拟中断扩展(PLICv Pure Virtual Interrupts Extensions)

With direct access to claim/complete registers at the guest level, injection of purely virtual interrupts must also be done through the PLIC, so there are unified and consistent forwarding and handling for all the vhart’s interrupts.

由于即便是通过直接访问 Guest 层面的声明/完成寄存器来注入纯虚拟中断,也必须通过 PLIC 完成,因此对所有 vhart 的中断都需要有统一的、一致的转发和处 理。

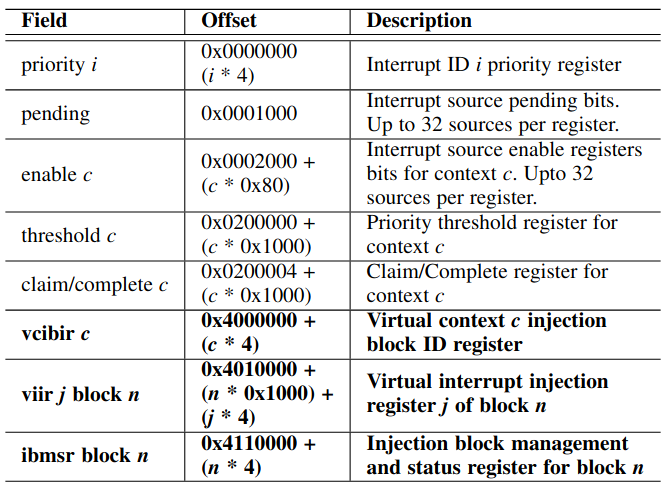

TABLE 3: Extended memory map for the virtualization-aware PLIC. In bold, the new virtual interrupt injection registers.

表 3. 用于虚拟化可感知的 PLIC 的内存映射。粗体表示新的虚拟中断注入寄存器。

Fig. 7: PLIC microarchitecture with virtualization enhancements. Architectural changes to include support for virtual interrupt injection are highlighted in blue.

图 7. 具有虚拟化增强功能的 PLIC 微架构。包括对虚拟中断注入的支持的架构更改以蓝色突出显示。

To this end, and inspired by Arm’s GIC list registers, we added three new memory-mapped 32-bit wide register sets to the PLIC to support this operation (see Table 3 and Fig. 7): Virtual Interrupt Injection Registers (VIIR), Virtual Context Injection Block ID Registers (VCIBIR), and Injection Block Management and Status Registers (IBMSR).

为此,在 Arm 的 GIC 列表寄存器的启发下,我们向 PLIC 添加了三个新的内存映射的 32 位宽度寄存器集合以支持此操作(参见表 3 和图 7):

- 虚拟中断注入寄存器(VIIR);

- 虚拟上下文注入块 ID 寄存器(VCIBIR);

- 注入块管理和状态寄存器(IBMSR)。

VIIRs are grouped into page-sized injection blocks. The number of VIIRs in a block and the number of available blocks are implementation-defined (up to a maximum of 1,000 and 240, respectively); however, if a given block exists, at least one register must be implemented. There are GEILEN VCIBIR per-hart which are used to specify the source injection block used for a given context’s virtual interrupt injection.

VIIR 被分组为页面大小的注入块。一个块中的 VIIR 数量和可用块的数量是具体实现所定义的(这里最多分别为 1000 和 240);但是,如果存在给定块,则必须实现至少一个寄存器。每个 hart 的 GEILEN VCIBIR 用于指定用于给定上下文的虚拟中断注入的源注入块。

In this way, virtual inter-rupts for multiple harts belonging to a specific VM can be injected through a single injection block, precluding the need for complex synchronization across hypervisor harts. Also, this allows a hart to directly inject an interrupt in a foreign vhart without forcing an extra HS trap. Setting a context’s VCIBIR to zero indicates that no injection block is attached.

通过这种方式,属于特定 VM 的多个 harts 的虚拟中断可以通过单个注入块注入,从而无需跨 hypervisor 的 harts 进行复杂的同步。此外,这允许 hart 直接在外部 vhart 中注入中断,而无需强制执行额外的 HS 陷入。将上下文的 VCIBIR 设置为零表示未附加任何注入块。

PLICv 虚拟中断注入机制(PLICv Virtual Interrupt Injection Mechanism)

Virtual interrupt injection is done through the VIIRs which are com-posed of three fields: inFlight, interruptID, and priority. Setting the VIIR with a interruptID greater than 0 and the inFlight bit not set would make the interrupt pending for the virtual contexts associated with its block. The bit inFlight is automatically set when the virtual interrupt is pending and a claim is performed indicating that the interrupt is active, preventing the virtual interrupt from being pending. When the complete register is written with an ID present in a VIIR, that register is cleared, otherwise an interrupt might be raised to signal it, as explained next.

虚拟中断注入是通过由三个字段组成的 VIIR 完成的:inFlight、interruptID 和 priority。

使用大于 0 的 interruptID 设置 VIIR 并且未设置 inFlight 位将使与其块关联的虚拟上下文的中断挂起。当虚拟中断处于挂起状态并执行声明以指示中断处于活跃状态时,inFlight 位会自动设置,从而防止虚拟中断被一直挂起。当使用 VIIR 中存在的 ID 写入完成寄存器时,该寄存器将被清除,否则这个情况可能会引发中断,接下来会解释。

On a claim register read, the PLIC selects the higher priority pending interrupt of either a context’s injection block or enabled physical interrupts. Each block is associated with a block management interrupt (akin to GIC’s maintenance interrupt) fedback through the PLIC itself with implementation-defined IDs. It serves to signal events related to the block’s VIIRs lifecycle. Currently, there are two well-defined events: (i) no VIIR pending, and (ii) claim write of an non-present interruptID.

在读取声明寄存器时,PLIC 选择会选择被挂起的具有更高优先级的中断,这个中断可能是来自于一个上下文注入块或者是启用的物理中断。每个块都与一个块管理中断(类似于 GIC 的维护中断)相关联,该中断通过 PLIC 本身并以具体实现所定义的 ID(implementation-defined ID)进行反馈。它用于指示与块的 VIIR 生命周期相关的事件。目前,有两个定义明确的事件:

- 没有 VIIR 未决(pending);

- 声明了不存在的 interruptID 的写入。

The enabling of each type of event, signaling of currently pending events and complementary information are done through a corresponding IBMSR. Note that all of the new PLIC registers are optional as the minimum number of injection blocks is zero. If this is the case, a hypervisor might support either (i) a VM with only purely virtual interrupts, falling back to the full trap-and-emulate model, or (ii) a VM with only physical interrupts.

每种类型的事件的启用、当前未决事件的信号和补充信息都是通过相应的 IBMSR 完成的。请注意,所有新的 PLIC 寄存器都是可选的,因为注入块的最小数量为零。如果是这种情况,hypervisor 可能支持以下两种情况:

- 仅具有纯虚拟中断的 VM,回退到完全的陷入和模拟模型;

- 仅具有物理中断的 VM。

PLICv 上下文切换(PLICv Context Switch)

An important point regarding the PLIC virtualization extensions we have somewhat neglected in our design is its impact on vhart context-switch. At first sight, it might seem prohibitively costly due to the high number of MMIO context and block registers to be saved and restored.

关于 PLIC 虚拟化扩展,我们在设计中有些忽略的重要一点是它对 vhart 上下文切换的影响。乍一看,由于要保存和恢复大量 MMIO 上下文和块寄存器,它的成本可能会高得令人望而却步。

However we believe this is minimized first (i) due to the possibility of having up to GEILEN virtual con-texts for each hart and a number of injection blocks larger than the maximum possible number of active vharts; second (ii) we expect that only a small number (1 to 4) VIIRs are implemented in each block; and third (iii) as we expect that physical interrupt assignment will be sparse for a given virtual machine, an hypervisor can keep a word-length bitmap of the enable registers that contain these interrupts, and only save/restore the absolutely needed.

然而,我们认为这这个成本会被最小化:

- 因为每个 hart 可能有多达 GEILEN 个虚拟上下文,并且注入块的数量大于活跃 vhart 的最大可能数量;

- 我们预计每个区块中只实现少量(1 到 4)个 VIIR;

- 由于我们期望特定虚拟机的物理中断分配将是稀疏的,因此 hypervisor 可以保留包含这些中断的启用寄存器的字长位图,并且仅保存/恢复绝对需要的。

BAO RISC‑V 移植(BAO RISC-V PORTING)

Bao 的简介(注:此标题为译者添加)

Bao in a Nutshell. Bao [2] is an open-source static partitioning hypervisor developed with the main goal of facilitating the straightforward consolidation of mixed-criticality systems, thus focusing on providing strong safety and security guar-\antees. It comprises only a minimal, thin-layer of privileged software leveraging ISA virtualization support to partition the hardware, including 1-to-1 virtual to physical CPU pinning, static memory allocation, and device/interrupt direct assignment. Bao implements a clean-slate, standalone component featuring about 8 K SLoC (source lines of code), which depends only on standard firmware to initialize the system and perform platform-specific tasks such as power management.

简而言之,Bao [2] 是一个开源静态分区 hypervisor,其主要目标是促进混合关键性系统的直接整合,从而专注于提供强大的安全保障。它仅包含一个最小的、很薄的的特权软件,利用 ISA 虚拟化支持对硬件进行分区,包括 1 对 1 的虚拟 CPU 到物理 CPU 绑定、静态内存分配和设备/中断直接分配。Bao 实现了一个全新的独立组件,具有大约 8K SLoC(源代码行),它仅依赖于标准固件来初始化系统并执行特定于平台的任务,例如电源管理。

It provides minimal inter-VM communication facilities through statically configured shared memory and notifications in the form of interrupts. It also implements from the get-go simple hardware partitioning mechanisms such as cache coloring to avoid interference in caches shared among the multiple VMs.

它通过静态配置的共享内存和中断形式的通知来提供最基本的 VM 间通信设施。它还从一开始就实现了简单的硬件分区机制,例如缓存着色,以避免多个 VM 之间共享的缓存受到干扰。

RISC‑V 的 Bao(Bao for RISC-V)

Bao originally targeted only Arm-based systems. So, we have initially ported to RISC-V using the QEMU implementation of the H-extension. Later, this port was used in the Rocket core with the extensions described in this article without any friction. Given the simplicity of both the hypervisor and RISC-V designs, in particular, the virtualization extensions and the high degree of similarity with Arm’s Aarch64 ISA, the port was mostly effortless.

Bao 最初只针对基于 Arm 的系统。因此,我们最初参考 QEMU 所实现的 H 扩展把 Bao 移植到了 RISC‑V。后来,这个移植在 Rocket 核心中使用了本文中描述的扩展,并没有任何兼容性的问题。考虑到 hypervisor 和 RISC‑V 设计的简单性,特别是虚拟化扩展以及与 Arm 的 Aarch64 ISA 的高度相似性,该移植几乎毫不费力。

It comprised an extra 3,731 SLoC compared to Arm’s 5,392 lines of arch-specific code. Nevertheless, a small step-back arose that forced the need to modify the hypervisor’s virtual address space mappings. For security reasons, Bao used the recursive page table mapping technique so that each CPU would map only the memory it needs and not map any internal VM structures besides its own or any guest memory. RISC-V impose some constrains given that each PTE must either serve has a next-table pointer or a leaf PTE. Therefore, we had to modify Bao to identity-map all physical memory, to enable performing software page walks to build guest page tables.

与 Arm 的 5392 行特定于架构的代码相比,它包含额外的 3731 SLoC。然而,出现了一个小的退步,迫使需要修改 hypervisor 的虚拟地址空间映射。出于安全原因,Bao 使用了递归页表映射技术,这样每个 CPU 将只映射它需要的内存,而不映射除了它自己的内存或任何 Guest 内存之外的任何内部 VM 结构。RISC‑V 施加了一些约束,因为每个 PTE 必须要么有一个下一个表指针,要么有一个叶 PTE。因此,我们不得不修改 Bao 以对所有物理内存进行 identity-映射,以便执行软件页面遍历来构建 Guest 页表。

Another RISC-V-specific facility we had to implement in Bao was the read guest memory operation. This need arose because neither QEMU nor our Rocket implementation of the H-extension provides the pre-decoded trapped instruction on htinst. Therefore, on a guest trap due to a page-fault that requires emulation (e.g., PLIC access), Bao must read the instruction from guest memory and decode it in software. Nevertheless, Bao never directly maps guest memory in its own address space. It reads the instruction via hypervisor load instructions. The RISC-V Bao port relies on a basic SBI firmware implementation featuring the IPI, Timer, and RFENCE extensions.

我们必须在 Bao 中实现的另一个 RISC‑V 特定功能是读取 Guest 内存的操作。之所以出现这种需求,是因为 QEMU 和我们的 H 扩展的 Rocket 都没有实现 htinst 上的预编码陷入指令。我们硬件上实现的功能验证是在 Verilator 生成的模拟器和 Zynq UltraScale+ 提供预解码的陷入指令。因此,在模拟 pagefault(例如,PLIC 访问)引起的 Guest 的陷入时,Bao 必须从 Guest 内存中读取指令并在软件中对其进行解码。

尽管如此,Bao 从不直接将 Guest 内存映射到自己的地址空间中。它通过 hypervisor 加载指令来读取指令。RISC‑V Bao 移植依赖于具有 IPI、定时器和 RFENCE 扩展的基本 SBI 固件实现。

As of this writing, only OpenSBI has been used. Bao provides SBI services to guests so these can program timer interrupts and send IPI between vharts. However, Bao mostly acts as a shim for most VS- SBI calls, as the arguments are just processed and/or sanitized and the actual operation is relegated to the firmware SBI running in machine mode.

在撰写本文时,仅使用了 OpenSBI。Bao 为 Guest 提供 SBI 服务,因此这些服务可以编程计时器中断并在 vhart 之间发送 IPI。然而,对于大多数 VS‑SBI 调用,Bao 主要充当一个很薄的中间层(shim),因为参数只是在 Bao 上经过处理和/或清理,实际的执行是转发给 machine 模式下运行的固件 SBI 进行的。

Bao 的 RISC‑V 限制(Bao RISC-V Limitations)

It is also worth mentioning there are still some gaps in the ISA to suors like Bao. For example, cache maintenance support operations are not standardized. At the moment, core implementations must provide this functionality via custom facilities. The Rocket core provides a custom machine-mode instruction for flushing the L1 data cache. As Bao relies on these operations to implement some of its features (e.g., cache coloring), we have implemented a custom cache flush API in OpenSBI that Bao calls when it needs to clean caches.

值得一提的是,Bao 上的实践反映了 ISA 上还存在一些差距。

例如,缓存维护支持操作没有标准化。目前,核心实现必须通过自定义的工具来提供此功能。Rocket 内核提供了用于刷新 L1 数据缓存的自定义 machine 模式指令。由于 Bao 依赖这些操作来实现它的一些特性(例如,缓存着色),我们在 OpenSBI 中实现了一个自定义的缓存刷新(cache flush)API 以便于 Bao 在需要清理缓存时进行调用。

Another issue regards external interrupt support. Due to the PLIC’s virtualization limitations (see Section 4.2), Bao’s implementation must fully trap and emulate guest access to the PLIC, i.e., not only on configuration but also on interrupt delivery and processing. As we show in Section 6.4, this adds significant overheads, especially on interrupt latency.

另一个问题与外部中断支持有关。由于 PLIC 的虚拟化限制(参见第 4.2 节),Bao 的实现必须将 Guest 对 PLIC 的访问完全陷入,并对此进行模拟,即不仅在配置步骤,而且在中断传递和处理上都需要进行陷入和模拟。正如我们在 6.4 节中所展示的,这会增加大量开销,尤其是在中断延迟方面。

Finally, Bao relies on IOMMU support to be able to directly assign DMA-capable devices to guest OSes. However, there is no standard IOMMU currently available in RISC-V platforms (see Section 8).

最后,Bao 依靠 IOMMU 的支持能够直接将支持 DMA 的设备分配给 Guest 操作系统。然而,目前在 RISC‑V 平台中没有可用的标准 IOMMU(参见第 8 节)。

评估(EVALUATION)

The evaluation was conducted for three different SoC configurations, i.e., dual-, quad-, and six-core Rocket chip with per-core 16 KiB L1 data and instruction caches, and a shared unified 512 KiB L2 LLC (last-level cache). The software stack encompasses the OpenSBI (version 0.9), Bao (version 0.1), and Linux (version 5.9), and bare metal VMs. OpenSBI, Bao, and bare metal VMs were compiled using the GNU RISC-V Toolchain (version 8.3.0 2020.04.0), with -O2 optimizations. Linux was compiled using the GNU RISC-V Linux Tool-chain (version 9.3.0 2020.02-2). Our evaluation focused on functional verification (Section 6.1), hardware resources (Section 6.2), performance and inter-VM interference (Sec-tion 6.3), and interrupt latency (Section 6.2).

评估是针对三种不同的 SoC 配置进行,即双核、四核和六核 Rocket 芯片,每核有 16KiB L1 数据和指令缓存,以及共享的、统一的 512 KiB L2 LLC(最后一级缓存)。软件栈包括了 OpenSBI(0.9 版本)、Bao(0.1 版本)和 Linux(5.9 版本)以及裸机 VM。OpenSBI、Bao 和裸机 VM 使用 GNU RISC‑V 工具链(8.3.02020.04.0 版本)进行编译,并进行了 ‑O2 优化。Linux 是使用 GNU RISC‑V Linux 工具链(9.3.0 2020.02‑2 版本)编译的。

我们的评估侧重于功能验证(第 6.1 节)、硬件资源评估(第 6.2 节)、性能表现与 VM 间干扰(第 6.3 节)和中断延迟(第 6.2 节)。

功能验证(Functional Verification)

The functional verification of our hardware implementation was performed on a Verilator-generated simulator and on a Zynq UltraScale+ MPSoC ZCU104 FPGA. We have developed an ad-hoc testing framework as a baremetal application. Our goal was to test individual features of the hypervisor specification without any additional system software complexity and following a test-driven development (TDD) like approach. During development, we have written a comprehensive test suite spanning fea-tures such as two-stage translation, exception delegation, virtual exceptions, hypervisor load-store instructions, CSR access, just to name a few.

我们的硬件实现的功能验证是在 Verilator 生成的模拟器和 Zynq UltraScale+MPSoC ZCU104 FPGA 上执行的。

我们开发了一个临时测试框架作为裸机应用程序。我们的目标是在没有任何额外系统软件复杂性的情况下测试 hypervisor 规范的各个功能,并遵循类似测试驱动开发(TDD)的方法。在开发过程中,我们编写了一个全面的测试套件,涵盖了两阶段翻译(two-stage translation)、异常委托(exception delegation)、虚拟异常(virtual exceptions)、hypervisor 加载 - 存储指令(hypervisor load-store instructions)、CSR 访问(CSR access)等功能,仅举几例。

To be able to test out individual features, the framework provides an API which easily allows: (i) fully resetting processor state at beginning of each test unit; (ii) fluidly and transparently changing privi-lege mode; (iii) easy access a guest virtual address with any combination of 1st and 2nd stage permissions; and (iv) easy detection and recovery of exceptions and later checking of its state and causes.

为了能够测试单个功能,该框架提供了一个 API,该 API 可以轻松实现:

- 在每个测试单元开始时完全重置处理器状态;

- 流畅透明地改变特权模式;

- 使用第一阶段和第二阶段权限的任意组合轻松访问 Guest 虚拟地址;

- 易于检测和恢复异常,随后检查其状态和原因。

Nevertheless, the framework still has some limitations such as not allowing user mode execution or experimenting with superpages. This hypervisor extension testing framework and accompanying test suite are openly available (https://github.com/josecm/riscv-hyp-tests) and can be easily adapted to other platforms. We have also run our test suite in QEMU, unveiling bugs in the hypervisor extension implementation, for which patches were later submitted.

尽管如此,该框架仍然存在一些限制,例如不允许 user 模式的执行和基于超级页面(superpage)的实验。这个 Hypervisor 扩展测试框架和附带的测试套件是公开可用的 (5),并且可以很容易地应用于其他平台。

我们还在 QEMU 中运行了我们的测试套件,发现了 hypervisor 扩展实现中的错误,后来提交了补丁。

As a second step to validate our implementation we have successfully ran two open-source hypervisors: Bao and XVisor [21]. XVisor also provides a “Nested MMU Test-suite” which mainly exercises the two-stage translation. At the time of this writing, our implementation fully passes this test suite. Some bugs uncovered while running these hypervisors were translated into tests and incorporated into our test suite.

作为验证我们实现的第二步,我们已经成功运行了两个开源 hypervisor:Bao 和 XVisor [21]。XVisor 还提供了一个 “Nested MMU Test‑suite”,主要用来测试两阶段翻译。在撰写本文时,我们的实现完全通过了这个测试套件。运行这些 hypervisor 时发现的一些错误被转化成测试用例,并合并到我们的测试套件中。

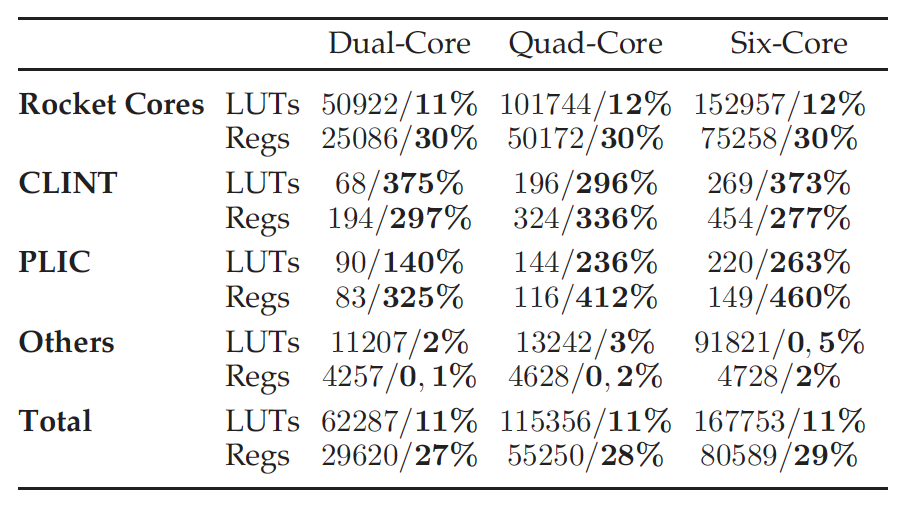

硬件开销(Hardware Overhead)

To assess the hardware overhead, we synthesized multiple SoC configurations with an increasing number of harts (2, 4, and 6). We used Vivado 2018.3 targeting the Zynq Ultra-Scale+ MPSoC ZCU104 FPGA. Table 4 presents the post-synthesis results, depicting the number of look-up tables (LUTs) and registers for the three SoC configurations. For each cell, there is the absolute value for the target configuration and, in bold, the relative increment (percentage) compared to the same configuration with the hypervisor extensions disabled. We withhold data on other resources (e.g., BRAMs or DSPs) as the impact on its usage is insignificant.

为了评估硬件开销,我们通过增加了 harts(2、4 和 6)的配置来考察多个 SoC 架构。我们使用针对 Zynq UltraScale+ MPSoC 的 Vivado 2018.3ZCU104 FPGA。表 4 显示了综合结果,描述了三种 SoC 配置下的查找表(LUT)和寄存器的数量。对于每个单元,都有目标配置的绝对值,以粗体表示与禁用 hypervisor 扩展的相同配置相比较计算出的相对增量(百分比)。我们没有提供有关其他资源的数据(例如,BRAM 或 DSP),因为他们的影响是微不足道的。

TABLE 4: Rocket chip hardware resource overhead with virtualization extensions.

表 4. 带有虚拟化扩展的 Rocket 芯片硬件资源开销。

According to Table 4, we can draw two main conclusions. First, there is an overall non-negligible cost to implement the hypervisor extensions support: an extra 11%LUTs, and 27-29% registers. Diving deeper, we observed that this overhead comes almost exclusively from two sources: the CSR and TLB modules. The CSR increase is explained given the number of HS and VS registers added by the H-extension specification. The increase in the TLB is mainly due to the widening of data store to hold guest-physical addresses (see Section 3) and the extra privilege-level and permission match and check complexity. The second important point is that, although the enhancements to the CLINT and PLIC reflect a large relative overhead, as these components are simple and small compared to the overall SoC infrastructure, there is no significant impact on the total hardware resources cost. Lastly, we can also highlight that increasing the number of available harts in the SoC does not impact the relative hardware costs.

根据表 4,我们可以得出两个主要结论:

对 hypervisor 扩展支持的实现具有不可忽略的总体成本:额外的 11% LUT 和 27‑29% 寄存器。深入研究,我们观察到这个开销几乎全部来自两个地方:CSR 和 TLB 模块。考虑到 HS 和 VS 的数量,这解释了 CSR 的增加是由 H 扩展规范添加的寄存器所致。而 TLB 的增加主要是由于扩大了数据存储空间以保存 Guest 物理地址(参见第 3 节),以及额外的关于特权级别和权限的匹配和检查所带来的复杂性;

第二个重要的观点是,虽然对 CLINT 和 PLIC 的虚拟化增强产生了较大的相对的开销,但因为这些组件和整体 SoC 基础设施相比,实现简单而且体积占比小,所以没有对总硬件资源成本产生很大影响。最后,我们还需要强调的是,增加 SoC 中可用 harts 的数量并不会影响相对硬件成本。

性能和虚拟机间干扰(Performance and Inter-VM Interference)

To assess performance overhead and inter-hart / inter-VM interference, we used the MiBench Embedded Benchmark Suite. MiBench is a set of 35 benchmarks divided into six suites, each one targeting a specific area of the embedded market. We focus our evaluation on the automotive subset. The automotive suite includes three high memory-intensive benchmarks, i.e., more susceptible to interference due to LLC and memory contention (qsort, susan corners, and susan edges).

为了评估性能开销和 inter‑hart / inter‑VM 的干扰,我们使用了 MiBench Embedded Benchmark Suite。MiBench 是一组 35 个基准测试,分为六个套件,每个套件一种针对嵌入式市场的特定领域。我们专注于我们的汽车子集的评估。汽车套件包括三个高内存密集型基准,即更容易受到来自 LLC 和内存竞争的干扰(qsort, susan corner 和 susan edge)。

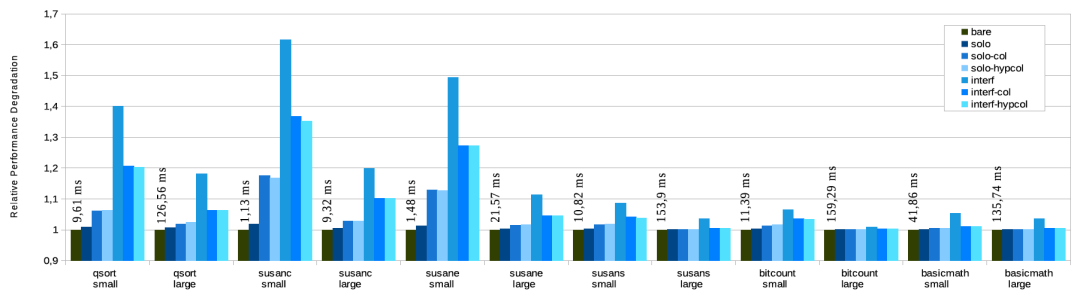

Each benchmark was ran for seven different system configurations targeting a six-core design: (i) guest native execution (bare); (ii) hosted execution (solo); (iii) hosted execution with cache coloring for VMs (solo-col); (iv) hosted execution with cache coloring for VMs and the hypervisor (solo-hypcol); (v) hosted execution under interference from multiple colocated VMs (interf); (vi) hosted execution under interference with cache coloring for VMs (interf-col); and (vii) hosted execution under interference with cache color-ing for VMs and the hypervisor (interf-hypcol).

每个基准测试都会运行在一个六核心设计的芯片的七种不同系统配置下:

- Guest 本机执行(bare);

- 托管执行(solo);

- 托管执行,对虚拟机进行缓存着色(solo-col);

- 托管执行,为虚拟机和 hypervisor 进行缓存着色(solo‑hypcol);

- 在多个托管 VM 的干扰下的托管执行(interf);

- 受虚拟机缓存着色干扰下的托管执行(interf‑col);

- 受虚拟机和 hypervisor 缓存着色干扰下的托管执行(interf‑hypcol)。

Hosted scenarios with cache partitioning aim at evaluating the effects of partitioning micro-architectural resources at the VM and hypervisor level and to what extent it can mitigate interference. We execute the target benchmark in a Linux-based VM running in one core, and we add interference by run-ning one VM pinned to five harts, each running a bare-metal application. Each hart runs an ad-hoc bare-metal application that continuously writes and reads a 1 MiB array with a stride equal to the cache line size (64 bytes). The platform’s cache topology allows for 16 colors, each color consisting of 32 KiB. When enabling coloring, we assign seven colors (224 KiB) to each VM. The remaining two colors were reserved for the hypervisor coloring case scenario.

具有缓存分区的托管场景旨在评估在 VM 和 hypervisor 级别上划分微架构资源的影响,以及它可以在多大程度上减轻干扰。

我们在只运行在一个核上的 Linux 虚拟机里,执行目标基准测试,同时,我们运行一个被固定到 5 个 hart 上的 VM,并增加 hart 间的干扰。在每个 hart 中都运行一个裸机应用程序。每个 hart 跑的是一个临时裸机应用程序:连续读写一个 1 MiB 数组,步长等于缓存行大小(64 字节)。该平台的缓存拓扑允许 16 种颜色,每种颜色由 32 KiB 组成。启用着色时,我们为每个 VM 分配了 7 种颜色(224 KiB)。剩下的两种颜色是为 hypervisor 着色用例场景保留的。

The experiments were conducted in Firesim, an FPGA-accelerated cycle-accurate simulator, deployed on an AWS EC2 F1 instance, running with a 3.2 GHz simulation clock. Fig. 8 presents the results as performance normalized to bare execution, meaning that higher values report worse results. Each bar represents the average value of 100 samples. For each benchmark, we added the execution time (i.e., absolute performance) at the top of the baremetal execution bar.

实验在 Firesim 中进行。Firesim 是一个 FPGA 加速周期精确模拟器,部署在一个 AWS EC2 F1 实例上,基于 3.2 GHz 模拟时钟运行。图 8 呈现了基于逻辑执行进行归一化的结果,这表示更高的数值体现了更差的结果。每个条形代表 100 个样本的平均值。对于每个基准,我们在裸机执行栏的顶部添加了执行时间(即绝对性能)。

Fig. 8. Relative performance overhead of MiBench automotive suite for different system configurations, relative to bare-metal execution. Absolute value indicated at the top of the solo bar.

图 8. 相对于裸机执行而言,不同系统配置的 MiBench 汽车套件的相对性能开销。solo 栏顶部指示的绝对值。

According to Fig. 8, we can draw six main conclusions. First, hosted execution (solo) causes a marginal decrease of performance (i.e., average 1% overhead increase) due to the virtualization overheads of 2-stage address translation. Second, when coloring (solo-col and solo-hypcol) is enabled, the performance overhead is further increased. This extra overhead is explained by the fact that only about half of the L2 cache is available for the target VM, and that coloring precludes the use of superpages, significantly increasing TLB pressure. Third, when the system is under significant interference (inter), there is a considerable decrease of performance, in particular, for the memory-intensive benchmarks, i.e., qsort (small), susan corners (small), and susan edges (small). For instance, for the susan corners (small) benchmark, the performance overhead increases by 62%. Fourth, we can observe that cache coloring can reduce the interference (inter-col and inter-hypcol) by almost 50%, with a slight advantage when the hypervisor is also colored. Fifthly, we can observe that the cache coloring, per se, is not a magic bullet for interference. Although the interference is reduced, it is not completely mitigated, because the perfor-mance overhead for the colored configurations under inter-ference (inter-col and inter-hypcol) is different from the ones without interference (solo-col and solo-hypcol). Finally, we observe that the less memory-intensive benchmarks (i.e., basicmath and bitcount) are less vulnerable to cache interference and that benchmarks handling smaller datasets are more susceptible to interference.

根据图 8,我们可以得出六个主要结论。

首先,托管执行(solo)导致性能略有下降(平均 1% 的开销增加),这是虚拟化两阶段地址翻译产生的开销;

其次,着色(solo‑col 和 solo‑hypcol)启用后,性能开销进一步增加。这种额外的开销可以这样解释:只有大约一半的 L2 缓存可用于目标 VM,并且着色排除了超级页面的使用,显著增加了 TLB 压力;

当系统(inter)存在显著干扰时,有相当大的性能减少,特别是对于内存密集型基准,如 qsort (small)、susan corners (small) 和 susan edge (small) 这三个基准测试。例如,对于 susan corners (small) 基准,性能开销增加了 62%;

我们可以观察缓存着色可以减少(inter‑col 和 hypcol)几乎 50%的干扰,当 hypervisor 也被着色时,还会额外有轻微的收益;

我们可以观察到缓存着色本身并不是解决干扰问题的灵丹妙药。虽然干扰减少了,但并没有完全消除,因为在干扰下的着色配置的性能开销(inter‑col 和 inter‑hypcol)与那些无干扰的配置(solo‑col 和 solo‑hypcol)不同;

我们观察到内存密集程度较低的基准(即基本数学计算和位计数)不太容易受到缓存干扰,处理较小数据集的基准更容易受到干扰。

The achieved results for RISC-V share a similar pattern to the ones assessed for Arm [2]. In our previous work [2], we have deeply investigated the micro-architectural events using a performance monitoring unit (PMU). As part of future work, we plan to conduct a deeper evaluation of micro-archi-tectural interference effects while proposing additional mech-anisms to help mitigate inter-VM interference.

RISC‑V 取得的结果与为 Arm [2] 评估的那些有相似之处。在我们之前的工作 [2] 中,我们已经通过使用一个性能监控单元(PMU)深入研究了微架构事件(micro-architectural events)。作为未来工作的一部分,我们计划对微架构进行更深入的干扰效应评估,并期望提出额外的机制以减轻 VM 间的干扰。

中断延迟(Interrupt Latency)

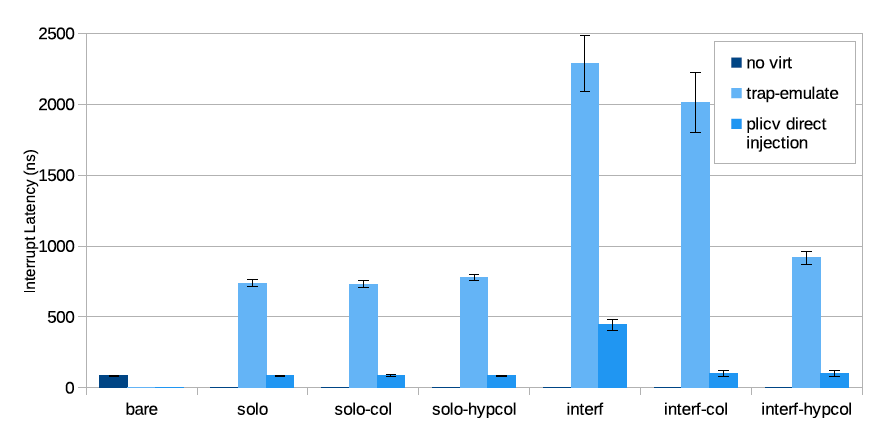

To measure interrupt latency and respective interference, we use a custom baremetal benchmark application and a custom MMIO, auto-restart, incrementing timer that drives a PLIC interrupt input line. This application sets up the timer to trigger an interrupt at 100Hz (each 10 ms). The latency corresponds to the value read from the timer counter at the start of the interrupt handler. We invalidate the L1 instruction cache at each measurement using the fence.i instruction as we believe it is more realistic to assume this cache is not hot with regard to the interrupt handling or the hypervisor’s interrupt injection code. We ran the benchmark using Firesim with the same platform and configurations described in Section 6.3. For guest configurations we took samples for both trap-and-emulate and PLIC interrupt direct injection.

为了测量中断延迟和相应的干扰,我们使用一个定制的裸机基准测试应用程序和一个定制的 MMIO,并设置了一个自动周期启动、不断增长的定时器来产生 PLIC 中断作为中断输入源。此应用程序设置定时器以 100Hz(每 10 毫秒)的频率来触发中断。延迟对应于在中断处理程序开始时从定时器计数器读取的值。我们使用 fence.i 指令在每次测量时使 L1 指令缓存无效,因为我们认为在中断处理或 hypervisor 的中断注入代码方面,更现实的假设是认为该缓存是 not hot 的。我们使用 Firesim 在第 6.3 节中描述的相同平台和配置中运行基准测试。对于 Guest 的配置,我们对陷入和模拟方法以及 PLIC 中断直接注入这两方面进行了采样。

The average of the results obtained from 100 samples (the first 2 discarded) for each configuration are depicted in Fig. 9. The interrupt latency for the bare (in Fig. 9, no virt) execution is quite low (approx. 80 ns) and steady. The trap-and-emulate approach introduces a penalty of an order of magnitude (740 ns) that is even more significant under interference (up to 2,280 ns, about 300%) both in average and standard deviation. Applying cache partitioning via coloring helps to mitigate this, which shows that most of the interference happens in the shared L2 LLC. The difference between inter-col and interf-hypcol shows that it is of utmost importance to assign dedicated cache partitions to the hypervisor: the interfering VM also interferes with the hypervisor while injecting the interrupt and not only with the benchmark code execution itself.

图 9 描绘了在每种配置下从 100 个样本(前 2 个丢弃)获得的结果的平均值。裸机(在图 9 中,没有 virt)执行的中断延迟非常低(大约 80 ns)并且很稳定。陷入和模拟方法引入了一个数量级的损失(740 ns),在平均偏差和标准偏差方面,在干扰(高达 2280 ns,约 300%)下,这种损失甚至更为显著。通过着色应用缓存分区有助于缓解这种情况,这表明大部分干扰发生在共享 L2 LLC 中。inter‑col 和 interf‑hypcol 之间的区别表明,将专用缓存分区分配给 hypervisor 至关重要:干扰 VM 在注入中断时也会干扰 hypervisor,而不仅仅是基准代码执行本身会干扰 hypervisor。

Fig. 9. Interrupt latency in nanoseconds for baremetal execution and for guest execution with injection following a trap-and-emulate approach or direct injection with hardware support.

图 9. 裸机执行和 Guest 执行的中断延迟(以纳秒为单位),采用陷入和模拟方法进行注入,或通过硬件支持直接注入。

Fig. 9 also shows that the effect of the direct injection achieved with guest external interrupt and PLIC virtualization support can bring guest interrupt latency to near-native values. Furthermore, it shows only a fractional increase under interference (when compared to the trap-and-emu-late approach) which can also be attenuated with cache coloring. As the hypervisor no longer intervenes in interrupt injection, for this case, it suffices to color guest memory. A small note is that the use of cache coloring does not affect the benchmark for solo execution configurations, given that the benchmark code is very small. Thus, the L1 and L2 caches can easily fit both the benchmark and hypervisor’s injection code. Finally, we can conclude that with PLIC virtualization support, it is possible to significantly improve external interrupt latencies for VMs.

图 9 还显示了 Guest 外部中断直接注入和 PLIC 虚拟化支持所产生影响可以使 Guest 中断延迟接近原生值。此外,它显示在干扰下延迟仅有一小部分的增加(与陷入和模拟方法相比),这也可以通过缓存着色来进一步减小。由于 hypervisor 不再干预中断注入,因此在这种情况下,只需对 Guest 内存进行着色即可。需要注意的是,缓存着色的使用不会影响单独执行配置的基准,因为基准代码非常小。因此,L1 和 L2 缓存可以轻松适应基准测试和 hypervisor 的注入代码。

最后,我们可以得出结论,通过 PLIC 虚拟化支持,可以显著改善 VM 的外部中断延迟。

相关工作(RELATED WORK)

There is a broad spectrum of hardware virtualization related technologies and hypervisor solutions. Due to the extensive list of works in the literature, we will focus on (i) COTS and custom hardware virtualization technology and extensions and (ii) hypervisors and microkernels solutions for RISC-V.

目前已经有广泛的硬件虚拟化相关技术和 hypervisor 解决方案。由于文献中已有大量的工作,我们将重点关注:

- COTS 和自定义硬件虚拟化技术以及扩展;

- RISC‑V 上的 hypervisor 以及微内核方案。

硬件虚拟化技术(Hardware Virtualization Technology)

Modern computing architectures such as x86 and Arm have been adding added hardware extensions to assist virtualization to their CPUs for more than a decade. Intel has developed the Intel Virtualization Technology (Intel VT-x) [22], the Advanced Programmable Interrupt Controller (APIC) virtualization extension (APICv), and Intel Virtualization Technology for Directed I/O (Intel VT-d). Intel has also included nested virtualization hardware-based capabilities with Virtual Machine Control Structure (VMCS) Shadowing. Arm included the virtualization extensions (Arm VE) since Armv7-A and developed additional hardware to the Generic Interrupt Controller (vGIC) for efficient virtual interrupt management. Recently, Arm has announced a set of extensions in the Armv8.4-A that includes the addition of secure virtualization support [23] and the Memory System Resource Partition and Monitoring (MPAM)[24]. There are additional COTS hardware technologies that have been leveraged to assist virtualization, namely the MIPS virtualization module [25], AMD Virtualization (AMD-V), and Arm TrustZone [4], [26].

x86 和 Arm 等现代计算架构在添加额外的硬件扩展以支持其虚拟化的工作上已进行了超过十年。

英特尔开发了英特尔虚拟化技术(英特尔 VT‑x)[22]、高级可编程中断控制器(APIC)虚拟化扩展(APICv)和面向定向 I/O 的英特尔虚拟化技术(英特尔 VT‑d)。英特尔还将基于硬件的嵌套虚拟化功能集成在 Virtual Machine Control Structure (VMCS) Shadowing 之中。

Arm 上相关的工作包括自 Armv7‑A 以来的虚拟化扩展(Arm VE),和为了实现高效的虚拟中断管理给通用中断控制器(vGIC)开发的额外硬件。最近,Arm 宣布了 Armv8.4‑A 中的一组扩展,其中包括添加了安全虚拟化支持 [23] 和内存系统资源分区和监控(MPAM)[24]。还有其他 COTS 硬件技术也已被用来辅助虚拟化,如 MIPS 虚拟化模块 [25]、AMD 虚拟化(AMD‑V)和 Arm TrustZone [4]、[26]。

The academia has also been focused on devising and proposing custom hardware virtualization support and mechanisms [27], [28]. Xu et al. proposed vCAT [27], i.e., dynamic shared cache management for multi-core virtualization platforms based on Intel’s Cache Allocation Technology (CAT). With NEVE [28], Lim et al. developed a set of hardware enhancements to the Armv8.3-A architecture to improve nested virtualization performance, which was then included in Armv8.4-A.

学术界也一直专注于设计和提出自定义的硬件虚拟化支持和相关机制 [27]、[28]。徐等人提出了 vCAT [27],即基于英特尔缓存分配技术(CAT)的多核虚拟化平台的动态共享缓存管理。

通过 NEVE [28],Lim 等人为 Armv8.3‑A 架构开发了一套硬件增强功能以提高嵌套虚拟化性能,然后将其包含在 Armv8.4‑A 中。

Within the RISC-V virtualization scope, Huawei has also presented extensions both to the CLINT and the PLIC [29], including one of the timer extension proposals mentioned in section 4. Regarding the PLIC, comparing to our approach, their design is significantly more invasive and complex, as it uses memory-resident tables for interrupt/vhart and vhart/hart mappings. Their approach significantly complicates the PLIC implementation as it must become a bus-master. Nevertheless, this might bring some advantages, e.g., speeding-up VM context-switches. Furthermore, they also propose to extend the CLINT not only to include supervisor and virtual-supervisor timers but also to allow direct send and receive of HS/VS software interrupts (i.e., IPIs) without firmware/hypervisor intervention.

在 RISC‑V 虚拟化范围内,华为还提供了对 CLINT 的扩展和 PLIC [29],包括第 4 节中提到的定时器扩展提案之一。关于 PLIC,与我们的方法相比,它们的设计更具侵入性和复杂性,因为它使用内存驻留表进行中断/vhart 和 vhart/hart 映射。他们的方法使 PLIC 实现显著复杂化,因为它必须成为总线控制器(bus-master)。然而,这可能会带来一些优势,例如,加速 VM 上下文切换。此外,他们还建议扩展 CLINT,不仅包括添加 supervisor 和虚拟 supervisor 计时器的支持,还允许直接发送和接收 HS/VS 软件中断(即 IPI)并无需固件/hypervisor 干预。

RISC‑V 的 hypervisor 和微内核(Hypervisors and Microkernels for RISC-V)